The Disney-MGM Studio Backlot in Burbank

Part Two: Studio Execs Behaving Badly

by Todd James Pierce

In the early months of 1987, Burbank city officials worked toward an agreement with Disney to build a theme-park-slash-shopping-center in their downtown district, an agreement that would go through nine drafts. At issue was the money: Disney wanted to buy the land for next to nothing. Disney also wanted the city to pay for a parking structure large enough to hold 3,500 cars, which it would rent back from the city for roughly a million dollars a year. In February, when talking to the press, Disney CEO Michael Eisner hinted that a studio tour attraction might be built somewhere in Southern California: “We are pretty well committed in the Los Angeles area,” he told one reporter, “Orange County, the San Fernando Valley, Burbank and so forth—to creating a second attraction.” Though Eisner didn’t name the site under consideration, the reporter understood that any studio park in that area would put Disney into “head-to-head competition with MCA on both coasts.”

This offhanded remark didn’t go unnoticed at MCA, where they perceived that the Burbank proposal was intended to intimidate them. In talking with the New York Times, Jay Stein, President of MCA’s recreation division, conveyed that he believed the Burbank Studio Tour was “a way of making Universal hesitate about going ahead with its Florida park.” But Stein was not one to be threatened easily: he flourished in competitive environments, even when the odds were stacked against him. “We’re not afraid of Disney,” he told one reporter. “We’re ready to take them on.”

Jay Stein’s energetic bravado, in part, defined Universal’s strong-willed business culture for the public. But an unnamed former MCA-exec quoted by the Los Angeles Times put the problem in realistic financial terms: “If Disney drew off just 10% of MCA’s tour attendance here [in California], that could almost wipe out the tour’s entire profit margin.”

Three weeks after Eisner hinted that Disney would enter the studio tour market in California, MCA fired back, claiming that they now planned “a transformation of its 23-year-old Universal Studios Tour” in Hollywood. The key to this makeover would be four new attractions: an earthquake simulator, a Miami Vice stunt show, a ride based on E.T., and the Back to the Future Ride. The Earthquake simulator would be integrated into the studio tram tour, though unlike many previous effect offerings it would not educate guests as to how effects were achieved in the movies; that is, it would be pure entertainment much like attractions at Disneyland. Miami Vice would simply update the Universal stunt show offerings. But E.T. and Back to the Future would be arranged as stand-alone rides, something new to the Universal lot. These two attractions would wholly take their cues from Disney. E.T. would present an elaborate dark ride in which guests encountered audio-animatronic figures. The Back to the Future Ride would be arranged as a motion-picture-based flight simulator similar to—though not nearly as sophisticated as—the Star Tours project currently being developed for Disneyland.

When a reporter asked the price tag for these improvements, Gordon Armstrong, an MCA marketing executive, wouldn’t give a specific figure, except to say they would cost “tens of millions of dollars,” a figure that impressed the crowd, especially as Universal had a history of adding one or two small features to its park each year. “Basically, we are insuring our future by doing this,” Armstrong explained. “It is in response to the fact that the competition [for theme parks] in Southern California is the greatest in the world.”

Around the end of March—according to MCA exec, Jay Stein—Disney approached MCA with an offer so dirty that MCA would later refer to it as “blackmail tactics.” Disney sent an intermediary who was in close contact with a “high-ranking” executive to offer a deal: Disney would “withdraw from the Burbank plan if MCA would give up its proposed Florida studio tour.”

MCA, incensed, turned down the offer on principle.

On April 24, the Mayor of Burbank, Michael Hastings was invited to the Walt Disney Imagineering complex in Glendale to view tentative plans for the Burbank mall. He was surprised to see how much artwork filled the conference room. “Every little bit of wall space in that room was taken up with drawings, sketches and ideas,” he said. The drawings featured elaborate buildings, ornate street environments, and even a Ferris wheel. “My first reaction was, ‘I wonder where our stuff is, because this looks so tremendous, it can’t be for us.’ Then I began looking closer at the walls, and I saw the map of our property on the wall beside all these ideas.”

As the meeting progressed, his initial reaction of awe slowly darkened into another emotion: a sense of being overwhelmed. As he left the Imagineering complex, the elaborate plans caused him to have second thoughts about a Disney park in Burbank. Did the city really want a permanent carnival set up downtown?

Mayor Hastings took his doubts back to the city council, where he found that others shared his concerns. More than one council member wondered if a formal agreement with Disney would be in the best interest of the city. Some wanted to approach additional interested parties about developing a traditional mall project on the land, while others thought it might be in the city’s best interest to sell the property for more money than Disney was willing to pay.

The turning point came on April 28, when Eisner again invited city officials to his executive office. One other city where Disney had commissioned a report to explore the economic feasibility of building a Disney mall was Dallas. In 1984, Disney had developed plans to create the Texposition marketplace. During this meeting with Burbank officials, Eisner and Disney Vice President, Gary Wilson, played a videotape sent in by the city of Dallas. Professionally produced, the taped featured dozens of tuxedo-wearing youngsters, all of them begging Disney to build this unique indoor project in their town. It also featured business owners and civic officials asking Disney to come and build their project in Texas.

“Here we were in Burbank,” City Manager Bud Ovrom later reflected, “playing hard-to-get, and any other city in the country or the world would have given their eyeteeth for a Disney project. That tape opened our eyes.”

On Friday, May 1, 1987, Burbank officials held a meeting to discuss their plans to sell thirty acres of prime Burbank real estate to the Walt Disney Company for the ridiculously low price of 57 cents per square foot. The land was worth an estimated $20 per square foot—or $35m for the entire parcel. Disney would get the main parcel for a song, a mere $1m. It would also have the option of acquiring ten more acres for $8.7m, though Disney was still trying to fold the additional acreage into the $1m total sale price.

The official terms locked Burbank and Disney into a yearlong agreement: Disney had six months to develop designs and a construction plan and, if approved, six more months to revise them. If the revised plans were accepted, Disney would then be able to purchase the land for $1m.

But Disney wasn’t the only multinational company represented at the council meeting. Also in attendance were MCA lawyers who repeatedly objected to Burbank’s plan to partner with Disney. At stake was not just the land—but Disney’s intentions to build a studio-based theme park just five miles away from the Universal Studios Tour. Attorney Dan Shapiro asked the council: “There is a question whether this is the proper thing to do with city property without asking for competitive bids. You’re giving away 40 acres.”

“At $1 million,” City Manager, Bud Ovrom explained, “Disney is clearly getting a special price, but we would be getting a special project….The Disney Company has been talking about creating an all new ‘animal,’ which would combine the best aspects of a festival shopping center together with a significant entertainment element.” The project would combine theme park attractions from Disney-MGM Studios (then under construction in Florida) with a boutique shopping mall. “It is important to note,” he added, “that it would not be a ‘gated’ facility such as Disneyland or Magic Mountain.” Locals would be able to enter the main section of the mall without charge.

The following week, Michael Eisner announced that he would personally present Disney’s plans for the 40-acre site to the Burbank Redevelopment Agency, along with Imagineer Joe Rohde. But before Eisner could unveil his plans, details about the project began to leak out to the public. Some areas of the Backlot, insiders suggested, would be modeled after the Pleasure Island / West Side complex then being developed at Disney World. The Burbank project would include a number of specialty retail stores—similar to those slotted for the West Side shopping district—as well as rough copies of six Pleasure Island nightclubs. The clubs would be arranged on an upper floor in the Burbank complex, the shopping on a lower floor, to create a continuous club experience for one audience and a continuous shopping experience for another.

Surprisingly the big news about the Burbank project wasn’t leaked to the press in typical Disney fashion. The big news was kept under wraps until Eisner’s formal presentation.

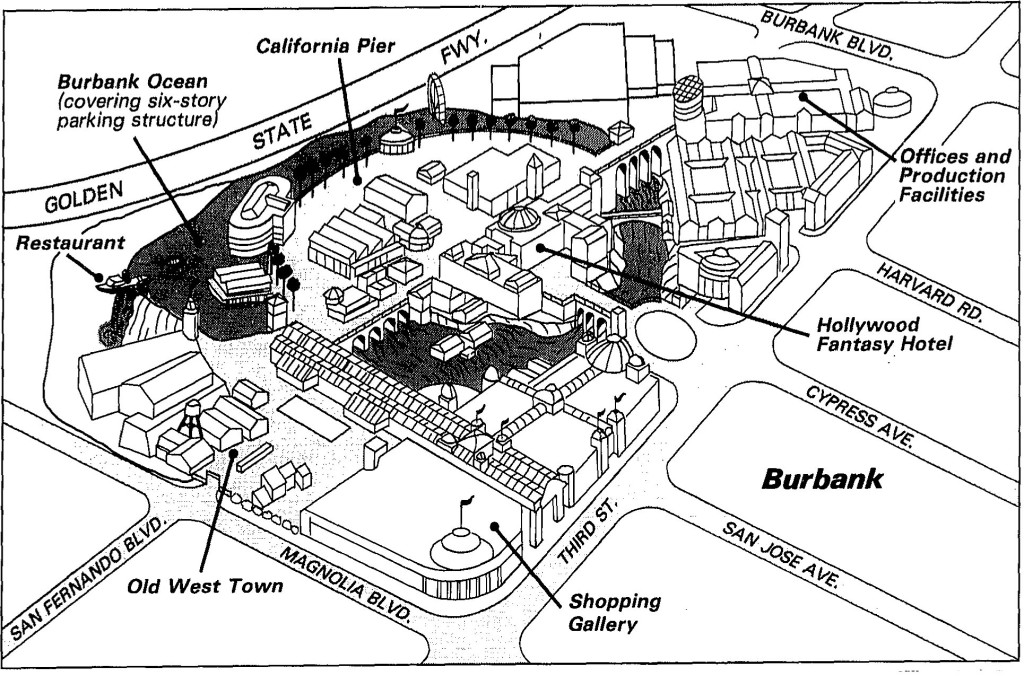

Standing before the Redevelopment Agency, Eisner explained that the project would be much more than a nightclub and shopping district. “This project will not be a second Disneyland in Southern California. Instead it will be a new generation of Disney attractions,” he announced. The complex would indeed include stores and nightclubs, but it would also include an enormous ride that would convey guests through famous movie sets. The proposed name for this attraction was “Great Moments in the Movies”—but basically, the attraction would be a California clone of the Disney-MGM showcase ride in Florida, later known as The Great Movie Ride.

The outdoor shopping areas would be themed like a movie lot: an old west outpost, a Sycamore-lined bungalow canyon, a New York street, a waterfront district, a European promenade, and an area designed after the Ginza shopping district in Tokyo. Furthermore, Eisner believed that they would also use these areas, from time to time, as a working backlot. He told the agency, “We’re going to use it as a movie set. So if you have a New York street….not only will it be a street for retail shopping, but when we have a movie that’s shooting—or MGM does or anyone does—they will use the New York Street [for production].” In essence, this would give the complex credibility as an actual studio location.

At the center of the development would be a 400-room Hollywood Fantasy Hotel—a Vegas-style highrise in which each floor was decorated according to a different Hollywood genre: such as the western floor, the space-adventure floor, a film noir floor, the New York gangster floor, and so on, with hotel employees dressed in matching costumes. At the top of the structure would be a domed restaurant, with windows opening to views of the city and the curved ceiling holding a planetarium-style star show.

In cooperation with the city, Disney would build a six-story parking facility, the top of which would hold a manmade lake called the “Burbank Ocean,” with a pier stretching out into the water. The “Ocean” would create an enormous 60-foot waterfall spilling down into another manmade lake. The waterfall would also partially screen the property from the nearby freeway.

At the edge of the waterfall would be positioned a boat-shaped restaurant, with its hull pushed partially over the top of the falls, like a balcony sixty feet above ground. The “Fish Out of Water” restaurant inside would have an imaginative theme: it would be dressed as a Boston seafood shack that only sold steaks, as though cows were some new form of marine life. On its walls would be photos of marine biologist Jacques Cousteau filming a documentary on the life of sea cattle. Other photos would show cows playing with seals and swimming beside fish. One photo would feature Ernest Hemingway catching a Bison with a fishing line. Above it all, hanging from the ceiling would be twelve foot-long lobster traps, perfectly sized for cattle.

But the most impressive news concerned the operations of the Disney studio. The Disney-MGM Backlot would include a new TV studio and tour. Eisner also planned to move the animation department—or at least one of its units—to the Backlot so that park guests could tour a working animation facility. They would also be able to visit an archival museum that would present the Walt Disney story. To round out the studio offerings—and perhaps to make the complex feel more like a Universal-style park—Disney would include a stage show that demonstrated how three-camera TV shows were produced, allowing members of the audience to participate in a simulated drama.

Lastly Disney would adapt its new simulator ride—the system used for Star Tours—to create a theater-based attraction to demonstrate how Hollywood created special effects in films. In essence, guests would both experience special effects in a simulator environment (such as a car chase) and then see how those effects were created (such as with the use of stuntmen and special vehicles).

The Redevelopment Agency was impressed. But Eisner’s plans only angered MCA—angered them to the point that Jay Stein took his “blackmail” story to the Los Angeles Times, explaining how Disney had used a runner to suggest a dirty trade: Disney would leave Hollywood to Universal if Universal would leave Orlando to the Mouse.

The day after the “blackmail” story was published, Eisner shot back: “I have no idea what they [MCA] are talking about. Anything MCA does or does not do—or anything anybody else does or does not do—will not affect our plans.”

Disney studio executive, Jeffrey Katzenberg piled into the fight, adding, “It sounds to me like it’s sour grapes.”

But Jay Stein held to his original story, telling the press: “There is no doubt in my mind what happened.” Garth Drabinsky, president of Cineplex Odeon, MCA’s partner on the Florida project, also chimed in: “The communication was made to the venture,” he said, though he declined to name the intermediary who communicated the deal.

Frustrated and belittled, MCA announced that they intended to file a lawsuit to stop the Disney development in Burbank. Acting as though MCA had the best interest of local residents at heart, Stein told reporters: “If I were on the Burbank City Council, I would not have insulted the taxpayers of Burbank by offering a piece of land for $1 million that I would conservatively say really costs $50 million. If anyone should be outraged, it’s the citizens of Burbank.”

In a separate interview, Stein hinted that the real problem was that Disney, not MCA was getting an exclusive deal on prime real estate: “What Disney is proposing is outrageous. They want a free option for a year on 40 acres of prime real estate, plain and simple.”

But in LA Superior Court, MCA didn’t just file one lawsuit. They filed two. The first claimed that the secret negotiations between Disney and Burbank violated the Brown Act, which “prohibits city councils, school boards and other governmental agencies from meeting on public issues in private, except in certain circumstances, including land negotiations.” The remedy for this, they claimed, was for the court “to invalidate the agreement between Burbank and Disney.” The second lawsuit argued that the contract between Burbank and Disney should be invalidated because the city had not completed the proper environmental studies to determine the impact of a Disney development within city limits. The suit went so far as to suggest that the proposed park might have a “profound, adverse impact” on the region. Though the suits appealed to parity and environmental issues, the underlying motivation was clear: these were legal maneuvers to prevent Disney from stealing potential customers from the Universal Studios Tour.

Over the following week, newspapers and business journals around the nation would feature articles about the MCA lawsuits, most all of them citing the legal action as the latest development in a growing feud between Disney and MCA. The lawsuits had one unintended affect: it further united Disney and Burbank as partners. One Burbank official would say that the legal action was perceived as “nothing more than an effort by MCA to harass their rivals at Disney.”

With Disney and Burbank wedded to this new project, MCA was left out in the cold, with few places to turn.

=== === === === ===

Next Week: Chapter Three – Behold the Studio Backlot!

Also Available On The DHI Podcast

=== === === === ===

This article is part of the DHI reboot: From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts each week. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success.

This article is part of the DHI reboot: From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts each week. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success.

I should also point out that this DHI multi-part article is a substantial expansion to the original Disney/Universal article on the Studio Backlot that I wrote for Jim Hill Media in 2008. In the past eight years, I’ve discovered many more elements that contribute to this fascinating story. The original article, clocking in at twenty pages, is now over forty.

Lastly, even when things are slow on the blog, the DHI Facebook Group is always jumping. –TJP

I don’t unremarkably comment but I gotta state thaanks for the post on this amazing one :D.