Walt’s Final New Year’s – 1966

by Todd James Pierce

Here’s the part of the story that most people know:

On January 1, 1966, as Grand Marshall for the Tournament of Roses Parade, Walt Disney began his day early–very early–with a trip to the Wrigley Mansion to meet with the press and take photos. For the previous few years the Wrig ley Mansion, donated to the city, had served as the headquarters for the Tournament of Roses and was also the focal point for pre-parade activities.

ley Mansion, donated to the city, had served as the headquarters for the Tournament of Roses and was also the focal point for pre-parade activities.

As Rose Parade Queen, Carole Cota recalls: “Inside the toasty warm, Tournament of Roses-Wrigley Mansion, my Royal Court of Rose Princesses and I were positioned in the living room, in front of the welcoming fireplace with our Grand Marshal, Walt Disney, set to begin more official photos. We had all arrived at 3:00am and I was joking with him after we were served just 1 oz. of orange juice to hold us over for the 5-mile, 2-hour Rose Parade.”

The events at the Wrigley Mansion lasted for a few hours, until sunrise burned across the horizon and revealed a few doughy clouds pressed into the sky. Cota remembers: “As we descended down the winding driveway to our respectful positions in the parade line-up and being met by throngs of reporters and photographers, Mr. Disney shared with me that he only agreed to be Grand Marshal on one condition, that all of his Disney characters could accompany him on the parade route while circling his official, rose-covered Grand Marshal’s car.”

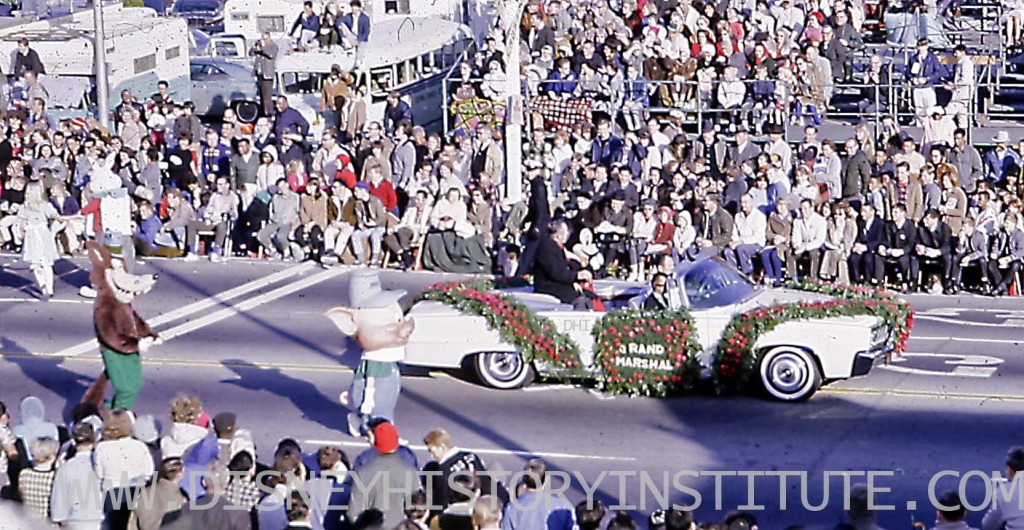

The parade began shortly after eight, a little earlier than initially planned. Though the crowd was expecting rain–and dressed for it–the day was cold but sunny. Walt rode alongside his best known creation, Mickey Mouse, rather than following the tradition of including family members in the Grand Marshal’s car. That day the Mouse was played by Paul Castle, the person Walt believed best portrayed Mickey in costume. Castle was often the suit actor when the Mouse accompanied Walt to special events, such as the opening of Anaheim Stadium. But twenty-two years later, Castle would claim that this event, was his favorite moment with Walt: “He was the grand marshal of the Rose Parade and I was in the car with him in the backseat. Just Walt and I for three hours. Just Walt and I. Of all the things I’ve done in my lifetime, that to me was my biggest day.”

The Grand Marshal’s car was followed by roughly two dozen costumed Disney characters, borrowed from the Entertainment division at Disneyland. But halfway down the five-mile route, the characters were switched out with fresh actors in costume, as a five-mile walk, even in winter, was considered too difficult for the costumed troupe to complete.

Behind the Grand Marshal’s car was also the City of Burbank’s float entitled “Our Small World of Make Believe.” The entry was a carefully arranged tribute to Disney’s work in Burbank, with the visual display encompassing three themes central to the studio’s identity: the frame structure for the float was an open book (indicating the importance of story); the visual centerpiece was a large musical clef (indicating the importance of song), and the unit was finished with a painter’s palette (indicating the importance of art). As with most parade entries, it was decorated with over 100,000 flowers, orchids and chrysanthemums in particular.

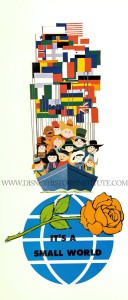

Earlier that year, Walt had been selected as Grand Marshal because–according to “Randy” Richards, President of the 77th Tournament of Roses–he represented t he good will and globalism that the parade hoped to embody. “In Walt we have a man whose name is a byword in nearly every household in the world,” he said. “He is without a doubt the most famous and respected man in the history of entertainment.” The theme of the parade was also “It’s a Small World,” a theme plucked from one of the attractions Disney had developed for the New York World’s Fair, an attraction that would soon open (expanded and enhanced) at Walt’s park in Anaheim. The parade’s logo that year–based on Disney art used for the Fair–was created at the studio and given to the Tournament committee, further cementing the visual connection between Disney and the 1966 parade.

he good will and globalism that the parade hoped to embody. “In Walt we have a man whose name is a byword in nearly every household in the world,” he said. “He is without a doubt the most famous and respected man in the history of entertainment.” The theme of the parade was also “It’s a Small World,” a theme plucked from one of the attractions Disney had developed for the New York World’s Fair, an attraction that would soon open (expanded and enhanced) at Walt’s park in Anaheim. The parade’s logo that year–based on Disney art used for the Fair–was created at the studio and given to the Tournament committee, further cementing the visual connection between Disney and the 1966 parade.

When a reporter asked him why he hadn’t previously been Grand Marshal, Walt responded, “I was always busy and then you have to meet so many people.” But in the weeks leading up to the parade, he had taken on the full responsibilities and met with hundreds, if not thousands of people in his role as Grand Marshal: he attended the participants’ dinner on December 2 and the Queen’s Breakfast on December 21, both held at the Huntington Hotel in Pasadena;  he invited the rose queen, tournament officials, and the Pasadena Junior Chamber of Commerce to the studio for a private tour and photo session on December 6; and, as was now the custom, he invited the two football teams and the rose court to a special event at Disneyland.

he invited the rose queen, tournament officials, and the Pasadena Junior Chamber of Commerce to the studio for a private tour and photo session on December 6; and, as was now the custom, he invited the two football teams and the rose court to a special event at Disneyland.

With thousands in attendance–and millions more watching the parade on TV–Walt rode down Colorado Boulevard in a white Chrysler convertible. With Mickey seated beside him, he was a representative of the California entertainment industry. He was also a representative of a growing philosophy of post-cold-war internationalism and optimism, a philosophy that Walt promoted in his films, TV shows, and parks. This philosophy, as embodied by Disney toward the end of his life, might be best exemplified by the phrase “peace through cultural understanding.”

The studio touches were focused at the start of the parade but not limited to the opening units. Elsewhere were individuals associated with–but not officially representing–Walt Disney Productions: Fess Parker (dressed as Davy Crockett) spearheaded the National Rifle Association’s entry, “Land of the Free, Home of the Brave,” and Art Linkletter (who had hosted both the 1955 opening and 1959 second opening of Disneyland for ABC) rode with his grandchildren atop the Farmers Insurance Group’s float, “Aladdin’s World of Magic.”

For most Disney fans, the story ends here, with Walt’s efforts as both a producer of family entertainment and an ambassador of global good will acknowledged before an admiring public. But Walt’s day did not end with the parade.

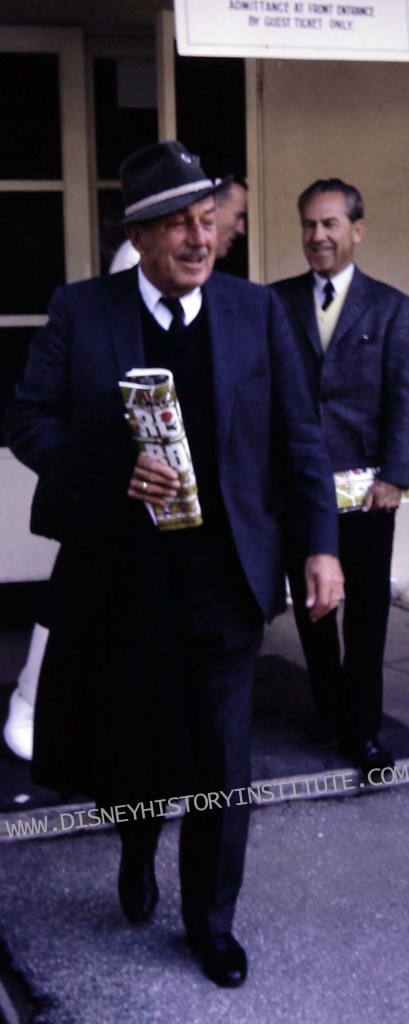

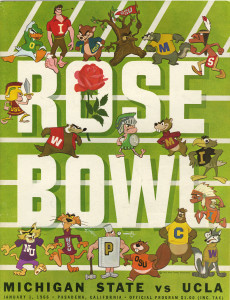

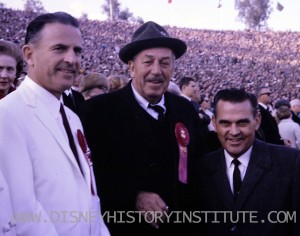

After the morning parade, Walt was driven to the Kiwanis Club luncheon at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium to kick off that afternoon’s Rose Bowl football festivities. During that event, along with the football coaches and the Tournament of Roses Queen, he briefly appeared on local TV and joyfully talked with journalists. As reporters asked him about his interest in the game, Walt joked around, explaining that he was a local boy at heart and therefore a fan of the UCLA Bruins (who faced off that afternoon against the  Michigan State Spartans). When asked if he had any advice for the Bruins, he said, simply, “Flubber gas,” a reference to the 1963 Disney film Son of Flubber, which included an extended comedic sequence involving a college football game. “What you do,” he chuckled, “is to fill the ball with Flubber gas, give it to the quarterback, then pass the quarterback instead of the ball. Then if there’s an interception, UCLA would still have the ball.”

Michigan State Spartans). When asked if he had any advice for the Bruins, he said, simply, “Flubber gas,” a reference to the 1963 Disney film Son of Flubber, which included an extended comedic sequence involving a college football game. “What you do,” he chuckled, “is to fill the ball with Flubber gas, give it to the quarterback, then pass the quarterback instead of the ball. Then if there’s an interception, UCLA would still have the ball.”

The good mood continued as he explained his connection to the university. Though he’d never completed high school, UCLA had once given him an honorary doctorate degree in the fine arts. Or as one reporter put it: “Disney mentioned an honorary degree ‘of some sort’ from UCLA as his primary reason for holding the Bruins ‘close to my heart.'”

in the fine arts. Or as one reporter put it: “Disney mentioned an honorary degree ‘of some sort’ from UCLA as his primary reason for holding the Bruins ‘close to my heart.'”

From there, Walt explained that he was originally a fan of the USC team, where he was once the president of a booster organization called the USC Trojaneers. When asked what the Trojaneers were, he dryly quipped: “It’s composed of men who didn’t go to college who give jobs to those who did, athletes particularly.”

And this perfectly explains the management of WED and Disneyland in the mid-1960s, as an organization who’d hired large numbers of USC football alums and transformed them into managers–including Dick Nunis, Orlando Ferante, Tommy Walker, and Walt’s son-in-law, Ron Miller.

Once the press event wrapped up, Walt continued out to watch the football game as a VIP guest in the stadium. Rose Parade Queen Carole Cota remembers that “Mr. Disney sat directly behind me on the 50-yard line, at the Rose Bowl game and was cheering for the UCLA Bruins.” The program (which Walt is holding in a number of these photos) includes artwork produced by the studio: both cover art representing various collegiate teams in cartoon form and internal comics featuring Disney characters (such as Donald Duck) humorously engaged in the sport. In the end, Walt’s chosen team, UCLA, would win. After the game, Walt would return to a temporary home on the other side of town.

The program (which Walt is holding in a number of these photos) includes artwork produced by the studio: both cover art representing various collegiate teams in cartoon form and internal comics featuring Disney characters (such as Donald Duck) humorously engaged in the sport. In the end, Walt’s chosen team, UCLA, would win. After the game, Walt would return to a temporary home on the other side of town.

In reviewing the events of this day, I’m reminded of two things:

(1) Walt attended a large number of prestigious events by himself in the 1950s and 1960s, without his family–including the opening of Disneyland. Though his wife Lillian was often his companion in the 1930s and 1940s, by the early 1950s, Walt was becoming an individual icon, with his family and work experiences often isolated from each other. During the 1966 Tournament of Roses Parade, the Disneys were remodeling their Holmby Hills house–and living elsewhere during the renovations. They were also expecting a new grandchild, which was one of the reasons why Lillian declined to attend. But fo ur days after the parade, Walt gave a more direct answer as to how his public and private lives had separated. When a reporter asked about the matter, Walt explained that the work on his home was “very upsetting. But I have nothing to say about this [home] project. That’s her business. She doesn’t interfere with mine, and I do the same by her.”

ur days after the parade, Walt gave a more direct answer as to how his public and private lives had separated. When a reporter asked about the matter, Walt explained that the work on his home was “very upsetting. But I have nothing to say about this [home] project. That’s her business. She doesn’t interfere with mine, and I do the same by her.”

And (2) though Walt didn’t yet know that cancer was building inside his lungs, surely it was there, the mass arranged as a tumor. His good mood and energy would endure for another five or six months. By mid-summer, he would be short on breath, clearly ill. That fall, part of his lung would be removed. In late September–at the  request of the Tournament of Roses Committee–Walt issued a statement about his experience in the parade. The statement reads, in part, “It was a distinct honor to be chosen Grand Marshal of the 77th Tournament of Roses Parade. This thrilling experience gave me a feeling of being surrounded by friends–not only those from this country but also the world over.” But as with many public statements issued near the end of his life, this one wasn’t actually written by Walt himself–rather by head studio publicist, Joe Reddy. It was reviewed by Walt–and hand-signed with his “OK.”

request of the Tournament of Roses Committee–Walt issued a statement about his experience in the parade. The statement reads, in part, “It was a distinct honor to be chosen Grand Marshal of the 77th Tournament of Roses Parade. This thrilling experience gave me a feeling of being surrounded by friends–not only those from this country but also the world over.” But as with many public statements issued near the end of his life, this one wasn’t actually written by Walt himself–rather by head studio publicist, Joe Reddy. It was reviewed by Walt–and hand-signed with his “OK.”

But the day commemorated in these stories and photos would be his final New Year’s Day: he was Grand Marshal for the Rose Parade; he was honored with his own float; his image was seen on TVs around the world, no one yet realizing that Mr. Disney was sick, that the year he started with such exuberance would also be his last.

<<<This article is also available as part of our DHI podcast>>>

<<<Click here for a visual history of Disney floats in the Rose Parade>>>

<<<A very special thanks to 1966 Rose Queen Carole Cota-Gelfuso for sharing her memories of the event>>>

==============

From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success. The next DHI posting will be a podcast–which will include interview clips with animators and engineers who worked with Walt. It will post in one week. And remember, even when things are slow on the blog, the DHI Facebook Group is always jumping –TJP

==============

Thank you again, Todd, for this fascinating story. I am so glad we have connected. Wishing you continued success and for 2016, may you enjoy the very best year of your life!

I read this article with interest, A lot of information I had no idea about included in this, keep up the good work.

This is really a great article. You note the Small World logo. The dolls would later be used on a commemorative stamp honoring Walt Disney. The rule with the U.S. Post Office at that time was that no copyrighted or protected images could be used. Therefore, they used the dolls as they had no copyright attached to them. I wonder if that didn’t factor as well, though it was just as well for Walt, since it allowed him to promote the new attraction that would grace Disneyland’s northern border.

I have that stamp

Wow Thanks!!

Wow Thanks!!

My Dad was the Commander of the Naval Recruiting Station where all the floats ended the Parade. Walt was kind enough to stay and watch part of the ending parade and have some traditional black eyed peas at the center. I have 10 to 20 pictures of him meeting and greeting guest, the best one was of my mom a former Miss University of South Carolina graduate escorting him through the building. I pull those pictures out every ten years or so just for the memories. Great writing.