The Frontierland That Never Was

by Todd James Pierce

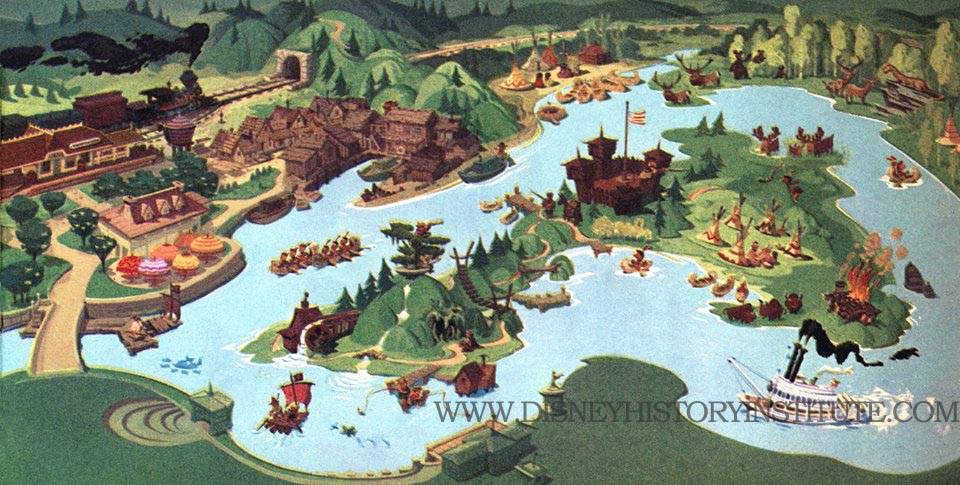

As I scooted around the Internet this week, I found many sites bemoaning the loss of Walt Disney’s original Frontierland. To make way for the two large show buildings in Star Wars Land, the park is permanently closing some rarely used areas of the western outpost. These include Big Thunder Ranch, its barbecue restaurant, the petting zoo, and the jamboree area. But some well-used parts of Frontierland will also be lost. There are four iconic areas that will be changed or removed: (1) Rivers of America will likely be shortened, with some mechanical wildlife retired or relocated; (2) the train tracks will no longer extend to the north perimeter of the park, (3) the back portion of Tom Sawyer Island (beyond the old fort) will be removed to accommodate a shorter river footprint; and (4) the Native American village with its animatronic figures will either be partially removed or relocated to another spot on the bank. The northern bend will instead feature a tall barrier cliff made of rocks with cascade waterfalls spilling down into the river. The train will also be repositioned on elevated tracks running above the stony shoreline, shortening its previous route to make way for Skywalker and friends. But we here at DHI aren’t just bemoaning the loss of the current Frontierland, we’re bemoaning the loss of the Frontierland that never was. By that, I mean River Town, an area that Walt announced in 1956 but then decided not to build.

But we here at DHI aren’t just bemoaning the loss of the current Frontierland, we’re bemoaning the loss of the Frontierland that never was. By that, I mean River Town, an area that Walt announced in 1956 but then decided not to build.

When Disneyland opened in 1955, most of Frontierland was consolidated in three areas: the Frontier fort (with the Pendleton shop and Golden Horseshoe Saloon), the riverfront (with the Mark Twain Steamboat and the original Indian Village) and the Painted Desert (with stagecoaches and pack mules traversing a re-creation of the old Southwest). Though many people now see the 1959 developments (with the monorail, Matterhorn, and Submarine Voyage) as the park’s first big expansion, Disneyland’s first large expansion actually took place in 1956 with most of the work directed at Frontierland.

To enlarge Frontierland, Walt focused on four areas: (1) a new Mine Train attraction would join the mules and stagecoaches on their trip through the Painted Desert, (2) the island in the middle of the river, empty for the park’s first year, would become a Tom-Sawyer-themed playground for children, (3) the Native American cultural village, originally located next to the Mark Twain landing, would be moved to the far side of the river, roughly where Splash Mountain now stands, and (4) the area next to Fowler’s Harbor, property now occupied by the Haunted Mansion, would be developed into a new themed area called River Town.

By summer of 1956 all of these elements were added to the park—except for one, River Town.

The idea for River Town likely came from the 20th Century Fox backlot. Many of Disneyland’s early art directors had experience on the Fox lot, including Dick Irvine, Sam McKim, and Bill Martin. These men understood Disneyland to be a series of permanent movie sets that represented the dominant genres of Hollywood entertainment, and as they designed the park—Frontierland, in particular—they often borrowed design elements from other studios. The Mark Twain riverboat and river at Disneyland were partially inspired by the Cotton Blossom riverboat on the MGM lot,  built in 1951. The Golden Horseshoe Saloon was inspired by the Golden Garter set originally designed on the Warner lot for Calamity Jane and Phantom of the Rue Morgue. But as Twentieth Century was home to many of Disneyland’s original designers, the massive Fox backlot also proved a type of general working model for sections of Disneyland. Like the MGM lot, the Fox lot had a steamboat and a western area, but it also had a River Town—which is an educated guess as to how a River Town, with its buildings composed of weathered wood, made its way into the designs for Walt’s park.

built in 1951. The Golden Horseshoe Saloon was inspired by the Golden Garter set originally designed on the Warner lot for Calamity Jane and Phantom of the Rue Morgue. But as Twentieth Century was home to many of Disneyland’s original designers, the massive Fox backlot also proved a type of general working model for sections of Disneyland. Like the MGM lot, the Fox lot had a steamboat and a western area, but it also had a River Town—which is an educated guess as to how a River Town, with its buildings composed of weathered wood, made its way into the designs for Walt’s park.

In his 1955 dedication speech Walt described Frontierland in the following way: “We will ride a covered wagon to a roaring river town, pay a visit to Slue Foot Sue’s Golden Horseshoe, and then catch the paddlewheel steamer Mark Twain for a trip down the Rivers of America.” But that description didn’t accurately describe the land he had built: there was a western town, but not a traditional river town. Early in 1956, he worked to correct that.

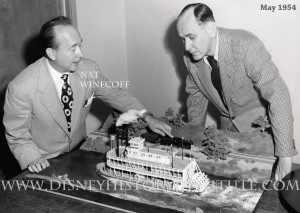

With guidance from Disney, Nat Winecoff—who worked as Walt’s executive assistant—set about to develop River Town, a collection of low wooden buildings that would separate the Plantation House restaurant (roughly where Pirates now stands) from the new Native American cultural village. River Town would be comprised mostly of shops, but there would be one small attraction, a Magnetic House.

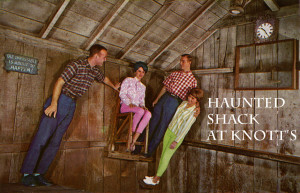

And what is a Magnetic House? Well, in the early 1950s a set of roadside attractions appeared in the U.S. in which structures, intentionally built on a slant, allowed visitors to see a set of visual illusions: water running uphill, chairs balancing by themselves on their back legs, and billiard balls curving in strange ways across a billiards table. There were a number of these “slanty shanty” magnetic houses in California, including The Mystery Spot in Santa Cruz (opened in 1941), Confusion Hill Gravity House in Percy (opened in 1949) and the Haunted Shack at Knott’s Berry Farm (opened in 1954). In River Town, Disney would build his own version of this slanting emporium of wonders in a little river village surrounded by small shops.

And what is a Magnetic House? Well, in the early 1950s a set of roadside attractions appeared in the U.S. in which structures, intentionally built on a slant, allowed visitors to see a set of visual illusions: water running uphill, chairs balancing by themselves on their back legs, and billiard balls curving in strange ways across a billiards table. There were a number of these “slanty shanty” magnetic houses in California, including The Mystery Spot in Santa Cruz (opened in 1941), Confusion Hill Gravity House in Percy (opened in 1949) and the Haunted Shack at Knott’s Berry Farm (opened in 1954). In River Town, Disney would build his own version of this slanting emporium of wonders in a little river village surrounded by small shops.

For the shops themselves, Winecoff directed Fred Schumacher, another early Disneyland exec, to develop a list of possible retail establishments to fill the area. His initial list was peppered with curiosity shops, including a Confederate Shop, a Gadget Shop and even a Pet Shop that might sell small turtles or lizards to children. The Pet Shop quickly was removed from the prospects, as “items sold here would be difficult for a patron to carry with them.” With the more exotic ideas excluded, the possibilities soon narrowed to those that might actually fill a mid-1800s river town. This list included a doll shop, a nut shop, a candle shop, a spice shop, a woodenwares shop, and possibly an old maps shop. In other words, Disney designers wanted to give River Town the feel of a reasonably accurate historic village.

All the shops would be small—between 200 and 400 square feet—similar to the smaller shops on Main Street. But unlike Main Street, where rents were roughly $20 per square foot, this back-of-the-park shopping village would have lower rates to account for the reduced foot traffic. Disney would charge either $6 per square foot or 25 percent of a shop’s monthly gross, whichever was greater. The term of the lease would be for one year, renewable, with a 30-day cancellation clause, which gave Disney flexibility to change shops—or perhaps even the whole area—if it so chose.

In late March and early April, Winecoff met with local business people to interest them in developing shops for River Town. He stressed that unlike traditional retail, these shops would need both showmanship and atmosphere to succeed. By April 13, he had a number of people tentatively interested in creating shops. These included a Doll Shop run by Christie Conway, President of the Doll Guild of California, a Curiosities Shop that would include small one-of-a-kind antiques, and a Gun Shop run by Hy Hunter, who had the largest personal gun collection on the west coast and also worked as a Hollywood importer of small fire arms from Germany. By one account his collection included tens of thousands of firearms, though admittedly, Disney was more interested in Hunter displaying his historic guns than selling them. In one memo cc-ed to Walt, Wincoff explained: “If we can get him to come in, his exhibit of guns would be quite a show in itself.”

By April 13, the team also had three firm proposals: Glenn Bever proposed to develop a Boat Shop that would sell model boats, ships in a bottle, and other nautical items; Harry Welch proposed a spice shop; and Frank Herman proposed a Good Hex Shop with lucky charms from all over the world. More so than the others, Herman fully grasped the concept of showmanship for his Hex Shop: his store would have a hand-cranked Hurdy-Gurdy that played stringed tunes with an otherworldly vibrato, a mechanical bulldog (who barked and growled) to scare away evil spirits, and an “Enchanted Talking Tea-Kettle” that told fortunes. “Ask it a question,” Herman explained to the Disney execs, “hold the spout to your ear and hear the answer.” The shop would sell Ouija boards, tarot cards, rabbits’ feet, fortune telling cards, four-leaf clovers, zodiac charts, and crystal balls.

By April 13, the team also had three firm proposals: Glenn Bever proposed to develop a Boat Shop that would sell model boats, ships in a bottle, and other nautical items; Harry Welch proposed a spice shop; and Frank Herman proposed a Good Hex Shop with lucky charms from all over the world. More so than the others, Herman fully grasped the concept of showmanship for his Hex Shop: his store would have a hand-cranked Hurdy-Gurdy that played stringed tunes with an otherworldly vibrato, a mechanical bulldog (who barked and growled) to scare away evil spirits, and an “Enchanted Talking Tea-Kettle” that told fortunes. “Ask it a question,” Herman explained to the Disney execs, “hold the spout to your ear and hear the answer.” The shop would sell Ouija boards, tarot cards, rabbits’ feet, fortune telling cards, four-leaf clovers, zodiac charts, and crystal balls.

On April 17 the Disneyland policy committee met to finalize the terms of a standard River Town lease, and the following day, Schumacher sent a memo to the entire Park Management and Operations Committee detailing exactly how River Town would be organized. Concept boards advertising the new area, with River Town highlighted, were positioned in the park.

But then an odd thing happened: nothing was built. Though work continued on the mine train and Tom Sawyer Island, no construction was started on River Town. Looking back, it’s hard to say why—though there is one small clue that might explain what happened to this collection of small shops and curiosities. One month later—in May 1956—shortly after brakes had been applied to the River Town project, Nat Winecoff began work on another area that, in the mid-1960s, would occupy some of the land originally earmarked for River Town: on May 3, 1956 Winecoff contacted the Association of Commerce in New Orleans to explain that, as the designers of Disneyland, they were interested in further developing the then-small New Orleans section of the park. In particular, Winecoff was interested in the names of “stores that manufacture or sell unusual pieces of merchandise typical of New Orleans.”

Years later, this line of research would produce New Orleans Square, which opened in 1966, a collection of small shops (each roughly 200 to 400 square feet) that in a historical setting sold merchandise typical of a town far from California.

But in getting back to the topic that began this article, Star Wars Land and the changes to Frontierland, maybe I should add a few more observations. The construction on Star Wars Land will change the footprint of the western area, removing part of one land that Walt had helped design. But Walt himself saw Disneyland as a park that was always developing: during his lifetime, he added to it every year. For me personally the small sense of loss I have about these changes isn’t focused on physical alterations to the park but rather on functional modifications.

In Walt’s lifetime Disneyland was an elaborate collection of movie sets representing popular genres, with park guest contributing to the atmosphere as a set of dress extras. Park guests were active co-creators in the environment: they rode the mules, became imaginary cowboys at the fort, climbed Castle Rock, rowed canoes, took minor roles in the Golden Horseshoe Revue, and danced a shuffle step as the Strawhatters laid down some jazz by the river. There are still areas in Disneyland that function under these rules, where guests themselves are as much of the show as they are the audience. But in Star Wars Land—at least what we know about it so far—guests will be more passive observers, much like moviegoers, with the entertainment arranged largely by technology, screens and architecture.

But along with this, I have a second observation: Star Wars Land also follows an impulse that influenced Walt in designs he oversaw for the park. Early park plans looked for popular genres in the film industry as a whole, not just with in the Disney library. In part, Walt looked to MGM for the steamboat and Warner for the Golden Horseshoe Saloon. His plans for River Town—though perhaps indirectly—were likely influenced by a set on the Fox lot. In creating Star Wars Land, current Disney designers are doing the same thing: they are looking to popular genres in contemporary films to expand the park, even when those films were started at other studios. Star Wars land will include two E-ticket attractions: in one, guests can pilot the Millennium Falcon on a secret “customized” mission; in the other, guests are placed into a “battle between the First Order and the Resistance.” In this way, Manifest-Destiny dreams of Frontierland will offer up a little dirt: the cowboy shoot outs that existed there in the 1950s will finally give way to more recent blaster battles that happened in another galaxy a long, long time ago.

But along with this, I have a second observation: Star Wars Land also follows an impulse that influenced Walt in designs he oversaw for the park. Early park plans looked for popular genres in the film industry as a whole, not just with in the Disney library. In part, Walt looked to MGM for the steamboat and Warner for the Golden Horseshoe Saloon. His plans for River Town—though perhaps indirectly—were likely influenced by a set on the Fox lot. In creating Star Wars Land, current Disney designers are doing the same thing: they are looking to popular genres in contemporary films to expand the park, even when those films were started at other studios. Star Wars land will include two E-ticket attractions: in one, guests can pilot the Millennium Falcon on a secret “customized” mission; in the other, guests are placed into a “battle between the First Order and the Resistance.” In this way, Manifest-Destiny dreams of Frontierland will offer up a little dirt: the cowboy shoot outs that existed there in the 1950s will finally give way to more recent blaster battles that happened in another galaxy a long, long time ago.

+++++

I’d like to thank my DHI colleague and master historian Paul Anderson for help on this article. Portions of it are related to research he shared with me a few years ago.

+++++

This article is included in the DHI Podcast as episode 015. Subscribe here. It’s free.

+++++

Also, this article is part of the DHI reboot: From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts each week. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success. The next DHI posting will be a podcast–which explores another piece of Frontierland that Walt envisioned but never built. It will post next week. And remember, even when things are slow on the blog, the DHI Facebook Group is always jumping. –TJP

Also, this article is part of the DHI reboot: From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts each week. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success. The next DHI posting will be a podcast–which explores another piece of Frontierland that Walt envisioned but never built. It will post next week. And remember, even when things are slow on the blog, the DHI Facebook Group is always jumping. –TJP

River Town was also no doubt influenced by Greenfield Vilkage and Colonial Williamsburg.

Absolutely! In the late 1950s, Walt travels a fair amount to historic towns and areas, particularly in the west. Frontierland picks up a number of ideas from these trips: the petrified tree, the mineral hall. Frontierland almost got a butterfly exhibit from the May Museum in Colorado. (I’m pretty sure some of the butterflies from the May Museum trip eventually showed up in Club 33 in glass frames.) But yeah, the park in Walt’s lifetime was very much a projection of Walt’s interests and experiences. I’m glad he had good taste.

I’ve got another reason why I’m pretty sure that the Fox lot played strongly into River Town. It’s part of another story that goes along with this one. I’ll post it up later this week–maybe next weekend.

Thanks for the note, Jeff. Much appreciated. Hope all’s well.

I found this really interesting. In the podcast, there’s a banjo version of the Star Wars theme. Is that available for purchase anywhere?

I too enjoyed the bluegrass version of John Williams’ Star Wars theme and Imperial March.

I also worked at the Haunted Shack at Knott’s Berry Farm in the late 80’s. I am glad Disney declined to reproduce the optical illusion house at Disneyland.

Todd, I am wondering if Walt ever visited or was aware of ‘Pioneer Village’ and assemblage of 19th century buildings transferred to the Kern County Museum in Bakersfield. It still stands and has many details found in Main street, Stores and restaurants, a dentist office, full size Oil Rig and many private homes. I think he would have enjoyed it!

There was a wall mounted collection of pistols, some with remarkable backgrounds . They were located in the first Frontierland Souvenier shop. The plaque said the collection was owned by George Eyster…..My name is Eyster so that factoid kinda stuck with me ….anyone remember ..?1950s…