|

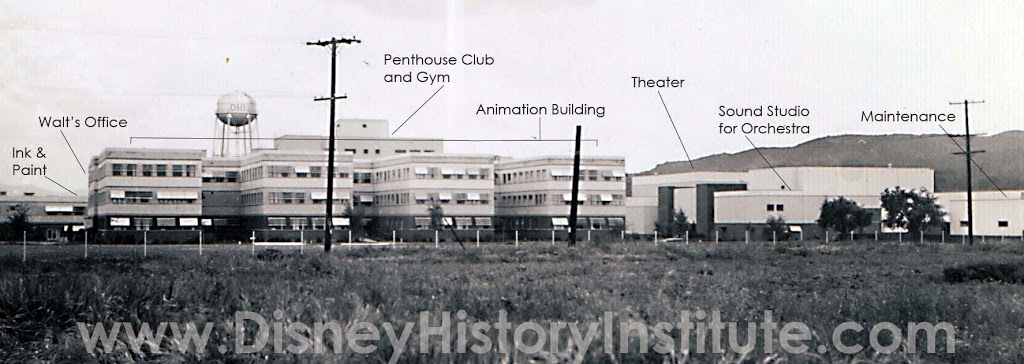

| Disney Studio 1941 |

[Note: This article is now available as a free audio download, DHI Podcast Episode 006. Subscribe through iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/disney-history-institute-podcast/id674703040?mt=2 ]

|

| Walt Disney in the Penthouse Club, 1960s, event unknown |

|

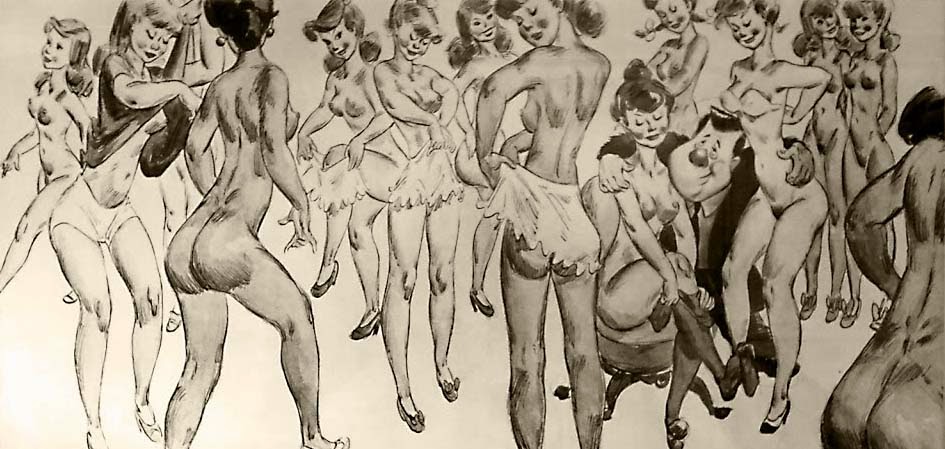

| Freddy Moore Mural at Penthouse Club |

|

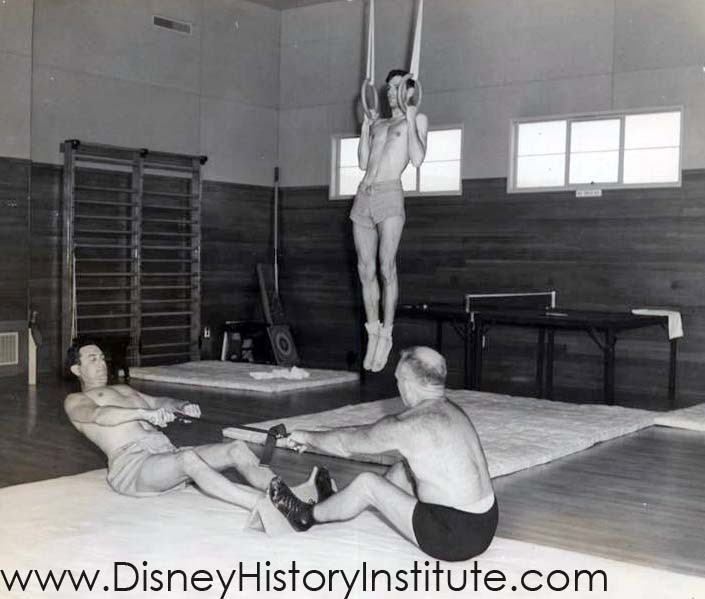

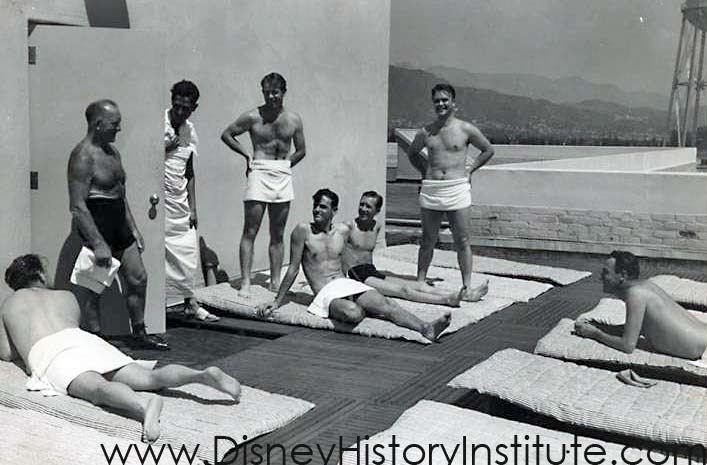

| Penthouse Gym – 1941 (possibly featuring Karl Johnson, right) |

When the Burbank studio opened in 1940, it contained three food service areas: the cafeteria, the semi-formal Green Room/Coral Room dining area, and the club. As animator Ollie Johnston recalls: “We could come up [to the Club] and get a milkshake or something to drink anytime you wanted, or get something to eat, or have traffic [i.e. a delivery boy] deliver it to your room…And gee, it was great.”

|

|

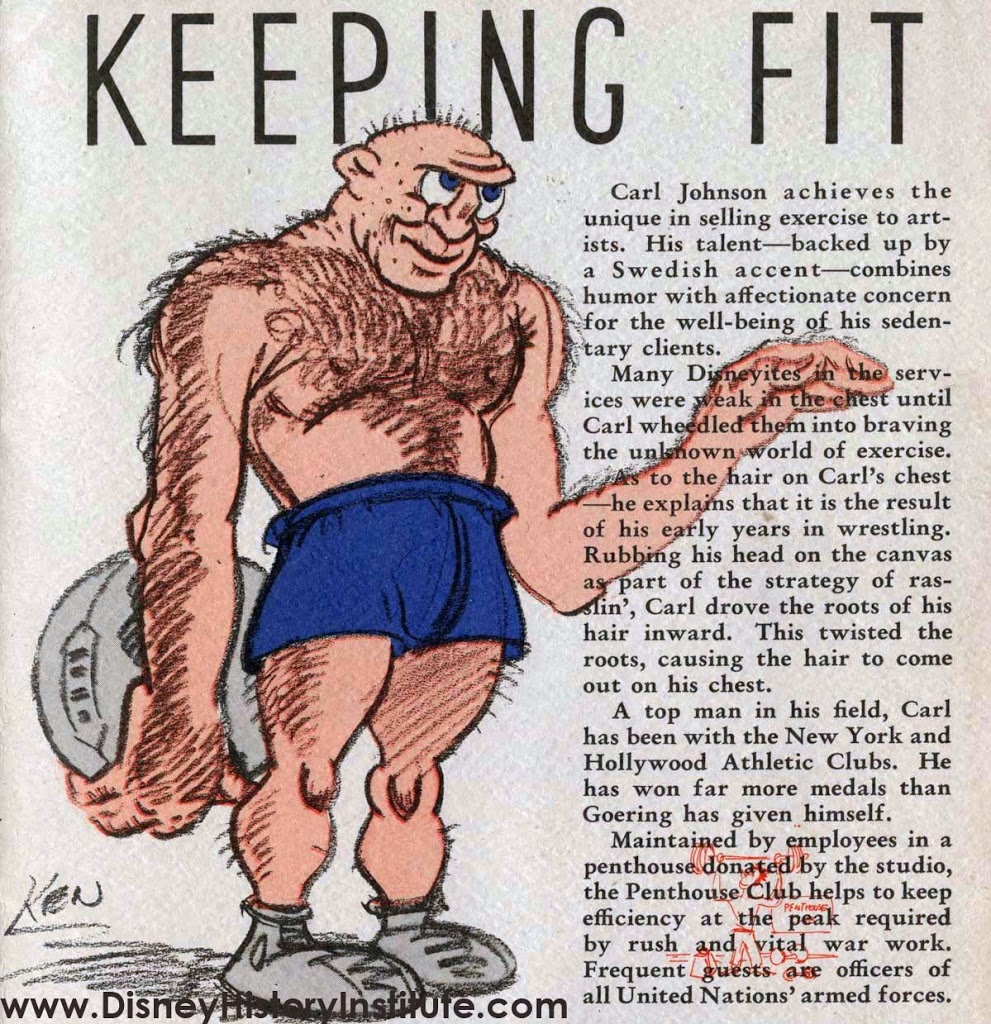

| Carl with a “C” in this Disney Dispatch, 1943 |

Regular exercise classes were led by Karl Johnson, a Swede who for a time was Walt’s personal trainer at the Hollywood Athletic Club. Even at the age of 60, Karl Johnson was a distinguished athlete—once a lightweight wrestler in the 1912 Olympics—who believed vigorous activity was essential for everyone. Once the Penthouse gym was open, he assisted artists with weights and stretches–artists that in one Disney in-house publication were called “sedentary clients.” One member recalls that Johnson was always available and that—as a peculiarity of his workouts—he used a 16-pound weight-lifting ball that he recommended for the abs and stomach. This same tongue-in-cheek publication explained that “Many Disneyites…were weak in the chest until Carl [sic] wheeled them into braving the unknown world of exercise.” These classes lasted until 1949, when, at the age of 66, Johnson retired from the company. [Note: Karl Johnson uses a “K” for his Olympic records, though some studio publications spell his name “Carl.”]

|

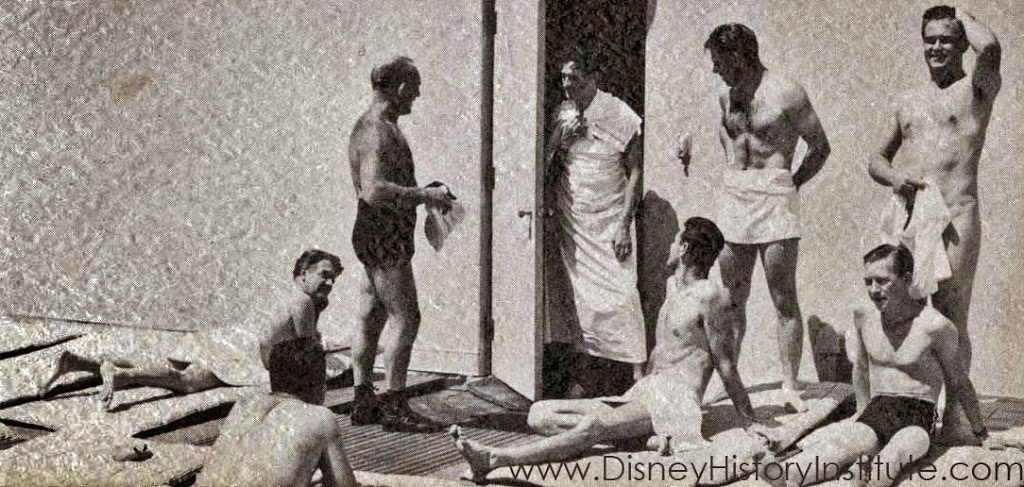

| Rooftop Sunbathing – 1941 |

Outside, on the rooftop patio, were tables and umbrellas, where the men could sit and talk. But the most popular activity, as described in a 1947 issue of New York Magazine, was sunbathing where “male employees acquire an all-over tan.” To put it more bluntly, as Milt Kahl’s assistant later recalled, “We used to take nude sunbaths, on the roof of the Studio, on our lunch hours and ‘chew the fat.'” This practice lasted for years, but eventually ended when nuns and nurses noticed naked men atop the studio. “St. Joseph Hospital was right across the street,” Layout artist Joe Hale recalls, “and they had built a new four-story wing on it. Anyway, it turns out that some of the nuns at St. Joseph’s were peering across the street, watching the guys…So when the word got around at the hospital about what the nuns were doing, Mother Superior or someone called over to the Studio and complained about the nude sunbathing. So they knocked that off.”

Disney artist Rolly Crump remembers that day in detail: “There was a notice as you were leaving the gym to go out on the roof that said, Don’t forget that they just built a hospital across the street.” But in Rolly’s memory, the artists didn’t knock it off right away. Even after the nun’s complained, the men continued to sunbathe nude–only they made sure to wear a towel whenever standing or in view of the hospital. “So we always put a little towel around us,” Rolly recalls, “whenever we went out there and lay naked.”

In the days that followed, one of the Disney artists even roughed out a gag drawing, one that was widely circulated among them men. In it, two cartoon nuns, with binoculars pressed to their eyes, gazed out hospital windows, their faces carved up with expressions of shock and intrigue.

Eventually, though, the men stopped bathing naked on the roof.

|

| A Slightly More Revealing Shot, Same Day, 1941. |

Aside from sunbathing and athletics, the club tended to bring its members more deeply into company culture, solidifying their social lives inside the studio. When Walt’s amusement park was nearly finished, he invited club members (and their children) out to Disneyland two weeks before it opened. On Monday July 4, 1955, about 200 people (members and children together) walked through Disneyland—or those parts of it that were finished. They rode the Jungle River ride (even though many of the animals were not yet installed on the river bank), with Walt himself narrating the adventure, then climbed aboard the stagecoach and Conestoga wagons. Walt, specifically, wanted to see how children would engage his park, as until then, its few visitors had mainly been adults.

|

| Walt Disney, 1960s, Penthouse Club, Event Unknown |

During the war the sick beds (or drunk beds) in the Club became temporary quarters for some of the officers that descended on the studio to make training films. “Accommodations were tough, really, in Los Angeles,” explains Erwin Verity, a Disney director and producer. “And they had to be here every day. In our little Penthouse Club upstairs, we had a couple of beds, and there were officers quartering themselves up there.”

|

||

| Walt Disney, 1963, Mousecar and Duckster Ceremony |

Lastly, a quick note: You can contact me through my personal webpage. My most recent book, THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success. You can find it on Amazon. And remember, even when things are a bit slow on the blog, the DHI Facebook Group is always jumping with new posts relating to the history of Walt Disney and the Walt Disney Company. –TJP

Wow that is crazy!! I never would have expected this.

UH…. I’m ……stunned!!!!

Consider that the Disney studio was largely filled with men and women who were art school graduates. At the studio, the culture often embraced an expansiveness of life and creativity that spiked out in many directions. Walt was smart enough to realize he would need to accommodate creative temperaments in many ways to produce films like Fantasia, Three Caballeros, etc., etc.