|

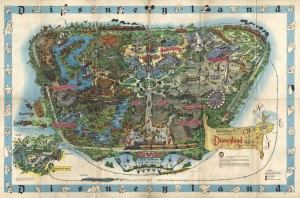

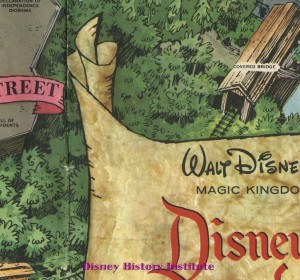

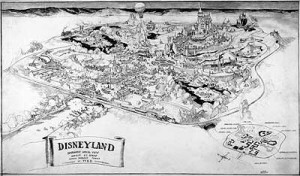

| Sam McKim Disneyland 1961 Souvenir Map. (Click On Image For Glorious Detail.) |

THE DISNEYLAND MAPS FEATURING

THE CARTOGRAPHY OF SAM McKIM

By Paul F. Anderson

Sorry for being absent from the airwaves for so long, I was otherwise preoccupied with some family matters. A few weeks ago, someone posted on the DHI Facebook page an image of an early Disneyland map, which resulted in a handful of questions. I began working on this piece when it was a bit timelier in regards to said event, but alas I am just now posting it. I would like to thank my fellow DHI partner in Disney history for so ably taking the helm during my absence.

THE DISNEYLAND MAPS

As a child, one of my all-time favorite Disneyland souvenirs was the map (still is–at least the vintage ones). As I set out on my path of preserving Walt Disney’s legacy through oral history, one of my all-time favorite WED Imagineers became Sam McKim, who as it turned out did the artwork for my favorite souvenir, the map. What follows is the story of the conjunction between Imagineer and Souvenir.

I first met Sam while working as a Disney historian and associate producer on the Emmy winning PBS documentary “Cartoon Mania!” My first of several one-0n-one interviews with Sam would follow shortly after that, in the fall of 1991. As I drove up the driveway of his beautiful Southern California home, the front door to the house popped open and out bounded Sam McKim. I was barely out of my car before he had snagged my hand with a vigorous shake and greeted me with “Glad to see you again!” There was no mistaking, he was genuinely happy to see me, and that he was anything but a gentleman. I remember thinking, “What a rare combination. An individual that is both creative and gifted as an artist, but also a refined and caring individual!”

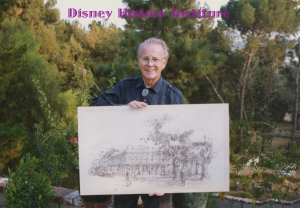

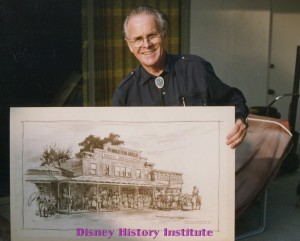

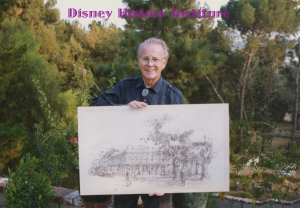

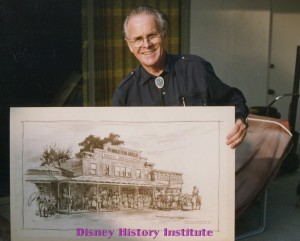

|

Sam McKim and a brown line of his art for Frontierland’s Golden Horseshoe Revue.

Taken in the early 1990s during my first interview with Sam at his home. |

Besides being extraordinarily talented, Sam was very affable and charitable, and most notably, he was excessively patient, as he gladly answered my numerous questions. In a pleasant and relaxed style this proud father shared his tales and memories as if they had happened yesterday. I found that our time together passed by effortlessly, as I became lost in his many stories of working for Walt. What makes this all the more amazing is that on this trip alone we spent over six hours together. And throughout this most pleasant afternoon and evening, the love of his life, Dorothy McKim, punctuated our conversations with fresh-from-the-oven snicker doodle cookies. I waxed rhapsodic (sincerely) about these cookies, and from that point on in my association with Sam and Dot McKim, every time (I mean every!) that I was to see them, Dorothy would have a batch of these cookies to give me (I’m not kidding!). This sweet gesture represented everything that the two of them were–caring, kind, giving, thoughtful, and truly meant for each other.

During our breaks this big-hearted man gladly pulled out volumes of his work for me to enjoy. Each piece of art had its own particular story and memory. He was kind enough to let me photograph each item, for which I realized I could only include a few in issues of Persistence of Vision. Now, with the Institute, and thanks to Sam’s willingness to share, I can showcase more of his amazing work.

I would see Sam and Dorothy at many of the Disney functions, and he would always have answers and thoughts on my often “very detailed” questions. I did conduct two more “substantial” interviews with him before he passed away in 2004, and I hope to make use of them here in future installments at the Institute!

What I remember most about Sam is that he was a giving man–and he gave liberally of himself. Because of that, my life has benefited–not only by learning more about Disney (as you are about to do), but also by experiencing his concern for the welfare of others and his kindness. I believe that observing these traits in others makes me a better person. If this is true, then I wish the world could have met Sam McKim–it would be a much better place for it.

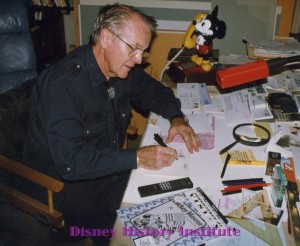

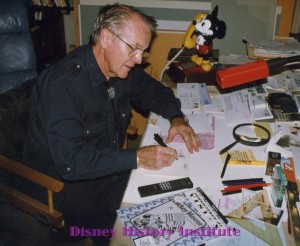

|

| Sam McKim making a special drawing of Lincoln for me, for a very special event! |

THE McKIM MAP INTERVIEW

THE FOLLOWING IS A SMALL EXCERPT FROM MY 1991 INTERVIEW WITH SAM, WHERE WE DISCUSS IN GREAT DETAIL THE CREATION OF THE DISNEYLAND MAP.

Paul F. Anderson: Tell me about the Disneyland map.

Sam McKim: Oh yes. Well, Herb Ryman kind of laughed at me when he found out I had the assignment. He said, “They wanted me to do that, and it’s too much work. You know it’s very detailed?”

Herbie was always kidding about things like this, but I started doing a layout. I was checking with all the key art directors around WED. I was doing it in pencil and I’d use two colors, an ocher yellow and a sky blue for the waterways. So you could look at all this pencil line without getting lost. You know you can get lost with pencil line if you don’t have some orientation shapes such as the water and the paths.

That’s how I did my initial rough. And I finished with this [showing finished map]. I started on it, I guess, at the Studio, and then took it home because they had other things for me to work on. I was doing this at home on my table in the bedroom. I had set it aside as a Studio project. When I was through with it, Ken Peterson, called me in to make sure that money wasn’t going to be spent needlessly. He told me to keep track of my hours, because they wanted me to finish it at work, you see, on my regular salary. And I said, “Well, I’ve put in enough hours that, at my hourly rate it would come to, I think about $700,” which wasn’t a great big piece at the time. He kind of chewed his lip, and thought about it, and finally I said, “Well cut that in half, and make it $350.” “All right,” he said.

PFA: Sounds like he jumped at your offer. Did you regret it?

SM: I said after that, “Boy, what a fool I am! I just cut things in half.” But that was my initial sketch, and I had done work for different people around there, including Ken, before at a really cheap rate. They would say, “Look, we don’t have much of a budget on this, but we’ll be able to pay you more than $5 a sketch.” I did several of those for Bill Boche and Ken Peterson. He [Ken] was sometimes tight with a dollar, but he was a good guy. And I consider him a friend. I even did a little freelance work for him after he retired. Later on they’d give me $15 to $20 a sketch, and you know it was extra beyond my paycheck. I was still working there, but if I wasn’t, I would probably have charged more. I was getting a fair amount.

PFA: How did you create the final art for the map after you finished this initial sketch?

SM: I used this original layout, which would have had value itself, but it was destroyed because I traced it down. I darkened the other side with graphite and I did the drawing.

PFA: But you weren’t the only one to work on this, were you?

SM: Well, at this time there were people that weren’t working, and Ken Peterson, who was in charge of background people and the rest, said, “I’ve got to put these people to work, Sam. We’re going to get Art Riley to do the color on this. You finished the black and white and did a good job on it, but we’re going to get him to color it on an overlay. So Art colored it. Also, a lot of people didn’t realize this at first, but all the little cartoon characters on the border I had taken off of model sheets. I thought I was going to do everything, the border, the color, everything, when I started, but Ken was saying, “We’ve got to use people, like X. Atencio, Bill Justice, and a lot of other people in animation.” Each one ended up doing two or three of these characters for the border, and they fit in according to my layout.

PFA: Did you go traipsing around Disneyland to get everything accurate and for inspiration, or did you do it all from WED?

SM: Well, I got research from WED, and everything I needed at that time. When you render certain things, there’s a looseness in the style that you use. But as long as you’re very close to that, you can interpret it, so it looks like a particular structure.

PFA: How long did it take you to do that first Disneyland map? After all, it is has a great deal of detail?

SM: I don’t know, I’d have to guess that maybe all the drawing could have been eight weeks or so.

PFA: So it consumed you for a good two months. Did Walt have any input on it?

SM: No, but he was aware of it. Ken Peterson would tell him everything that was happening on it. He had personal reports that he put in–and he was in charge of the map. There was another guy, Jack Olson, who was an assistant to the merchandise buyer at Disneyland. And he’d been at the Studio for a bit, then he went down to Disneyland. He took over the contact for the map afterwards. I updated it three times with different changes. And at the time of the changes, I believe I put the color on it as well. Then the printer was patching it and he’s going to make these lines just so and bring the colors in and balance it. Finally he said, “we’d better do a fresh one.” I said, “Hey, I can’t. I’m busy at work and I can’t do this at home.” I didn’t have the energy for it, and I think I was teaching at that time too. Then Colin Campbell made a map, the next one. And after that I think Charles Boyer at the park made one, and then he did another one. Before I retired I was starting to lay out a new map for Disneyland, but they had other projects going, and Marty was too busy to get together on this thing, so it just kind of sat there.

PFA: That’s too bad. Your map has become a classic among Disney enthusiasts. Would you have done anything different with the new map?

SM: Yes. I had a map that would fold out. The old map was reproduced down the middle. See if you can visualize what I’m doing. But from the centerline I take half a map and peel it back like turning a page of a book backwards. And then here turning the page front ways. And you’d see the new park underneath.

PFA: Wow! That would have been fantastic!

SM: And on either side, you could get an idea what the old map was like, and what the new one was like. And there was one of these versions I did of the new map–I gave them several things to choose from, and these were just line drawings that I did, they weren’t super careful, but they were careful roughs. And the other one was, this would fold out again, and as it folded out another time, these would be vignettes talking about Tomorrowland, or that part of Fantasyland up here on that side of the map. And over here it would be how things had changed in Adventureland and Frontierland and also anything along Main Street or what have you.

PFA: That would have been great! They never pursued it?

SM: No, they didn’t pursue it. And it was very involved–I’d rather have done just a single drawing. And I don’t know why I did it, but these were my ideas, to give them a unique type of map, give them the history. And it would cost them three times as much to print them, of course.

PFA: Your map has a very distinctive style. I don’t know what it is, but it sure plays well. The later maps–and I don’t want to take anything away from Charles Boyer or Colin Campbell–but your maps had a certain magic about them. As a child I would lay there in bed and just stare at your map–it was almost like being transported to Disneyland.

SM: Well, thank you.

PFA: You’re welcome. I am certainly not alone in this, as many people feel this way. With all the extravagant detail and bits of minutia, it must have been a ton of work. Was the map a job that you enjoyed?

SM: I managed to enjoy most of my assignments. You know you can’t go through life saying everything is wonderful and great and rosy and peachy and so on, because you get assignments that aren’t exciting. You get work jobs that have a lot of work to them, you know, and they don’t have that special extra appeal and feel of getting yourself lost in.

PFA: Did the map feel like that?

SM: Yes, it did. And my friend Herbie Ryman used to kid me a lot. He’d come around and say, “What do you have on your desk now, Sam?” He’d say, “You’re doing that? That’s so boring. I couldn’t continue with anything like this. How did they talk you into doing this?” I said, “Well, Herb, I guess no matter what kind of an assignment it is I try to make it interesting.” And he knew what he was getting at and I was getting at and he’d just josh me.

SAM McKIM MAPS BY THE NUMBERS

|

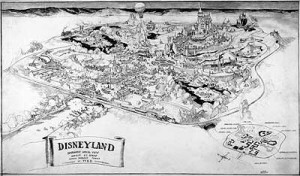

Walt Disney and Peter Ellenshaw’s map of

Disneyland. Pre-Opening postcard. |

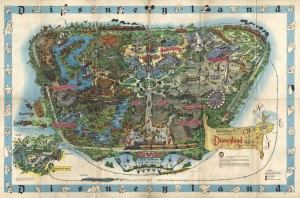

I whole-heartedly feel that one of the most iconic Disneyland souvenirs for Baby Boomers (and beyond) were the Disneyland souvenir maps. As children, it not only let us relive our visit to Disneyland, but it also allowed us to thoughtfully think and plan out our next visit. The labyrinthine detail contained in a McKim map was such, that hours upon end could be spent in the examination of every little bit and piece; often with the result of “How did I miss that?” There was so much contained within Walt’s Disneyland and it was so new to us, that the maps gave us an opportunity to explore Walt’s happiest place on earth in a way we could never quite achieve when in the park–inch by inch!

|

Herbert Ryman and Walt Disney

Proposal Map for Disneyland |

Walt Disney certainly liked large maps! Enough so that in September of 1953 he and Imagineer Herb Ryman worked seemingly nonstop to finish a map that Roy would take to New York to drum up the funds for Walt’s little project. With financing acquired, it was only a short half-decade before souvenir maps were sold in the park. The fact that they were not available on opening day (or in the following few years), suggests not a lack of interest, but a lack of time, artists, and funds. There were more pressing projects in the early days of Disneyland that required the attention of Walt and WED, so the souvenir maps were put on the back burner for a few years.

Towards the waning months of 1957, it became a priority, and Imagineer Sam McKim was given the assignment to create the first Disneyland souvenir map in his inimitable illustrative style. By the 1958 season, the map was available to park goers, not only in the shops, but also through mail order. This original map measured approximately 30″ x 45″, and early in 1958 was sold rolled up and inside a tube. The merchandising division learned quickly that this was not the optimal method for selling maps, and from that point on, all Disneyland souvenir maps were sold folded (in twelfths, measuring approximately 8″ x 15″ when folded).

With all the changes in store for 1958 and 1959, two additional maps were released shortly after this first map. They were almost identical to the original map, featuring an orange border and the 1958 copyright, but incorporated various additions (and subtractions) to Disneyland’s landscape (a mountain here, a Monorail there, a Viewliner no more, and so forth). Four more McKim Disneyland maps were released, one in 1961 (pink border), one in 1962 (blue border), and two in 1964 (green border). The last map features only minor cosmetic changes, and differs little from its 1964 counterpart.

By 1966 with Sam deep in other WED projects (primarily the 1964 New York World’s Fair and its aftermath at Disneyland), the map mantle was passed to Collin Campbell, which is a story for another day. (Although Sam did have one more map in him, when in 1993 he was called out of retirement in to create a souvenir map of Euro Disneyland.)

Today, the Disney History Institute celebrates the Disneyland maps of Sam McKim.

“DIAL M FOR MAP”

The Hitchcockian Appearance of Sam McKim

In cinema history circles it is a well-known fact that director Alfred Hitchcock made numerous “cameo” appearances in his films. For a brief moment, in 39 of his 52 major films, he can be seen in some sort of obscure extra role. Everything from boarding a bus, walking in front of a building, carrying a musical instrument (a favorite of his), or even appearing in a newspaper photograph.

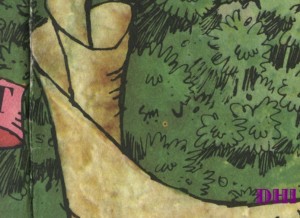

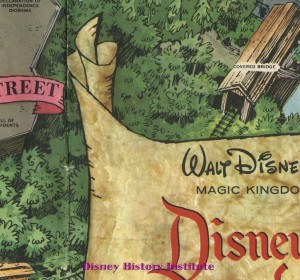

|

| Can you see it? |

One day when I was having dinner with the McKims, Sam told me about his version of this time-honored Hollywood tradition for the Disneyland map. Nestled secure and hidden within the trees of the cartographic minutia of the map, just a stone’s throw from the railroad’s Covered Bridge, and in perfect artistic harmony with the surrounding style, can be found the initials “SM”!

|

| A closer view! |

DISNEY LEGEND~BIOGRAPHY OF SAM McKIM

Sam McKim inspired many a Disney film and theme park attraction with his imaginative drawings. Yet, the actor-turned-artist is probably best known to Disney fans as the creator of the Disneyland souvenir maps, issued between 1958 and 1964. Even today, his intricate and fascinating maps remain among the most sought-after pieces of Disney memorabilia. In 1992, Sam’s cartography genius was encored when he created a new map in his unique style to commemorate the opening of Disneyland Paris.

Born in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1924, Sam moved to Los Angeles with his family during the Great Depression. At 10, he began working as an extra in movies with such Hollywood legends as Spencer Tracy, John Wayne and Gene Autry. Even then, Sam had a knack for art.

He said, “I was always drawing something or other. I’d draw caricatures of the actors and they would sign them for me.”

During high school he submitted some of his drawings to The Walt Disney Studios and was offered a job in the traffic department with an explanation that “the breaks would happen…later” Instead, Sam enlisted with the U.S. Army to fight in World War II with the American Infantry Division. Upon return, he enrolled at Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles and graduated in 1950, the day before he was drafted into the Korean War. After 14 months of service, he returned to the U.S. and attended Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles.

In 1953, Sam found himself having to decide between accepting a role in a John Ford movie or a job with 20th Century Fox making story sketches for films. He happily accepted the latter because “working behind the camera was what I really wanted to do.”

After a lay-off at Fox, in 1954, Sam joined Disney creating inspirational sketches for Walt’s new theme park – “Disneyland.” Among his first sketches were Slue Foot Sue’s Golden Horseshoe in Frontierland. He later contributed to Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln, Carousel of Progress, Pirates of the Caribbean and the Haunted Mansion. Eventually, every land at the Park benefited from Sam’s magic touch.

He also contributed to such Florida theme park attractions as the Hall of Presidents in the Magic Kingdom and Universe of Energy in EPCOT. Sam also developed inspirational sketches for the Disney-MGM Studios.

From time to time, Walt asked Sam to storyboard Disney films, as well. Among them are Nikki, Wild Dog of the North, Big Red, Bon Voyage, and The Gnome Mobile. He also developed storyboards for episodes of Disney’s television series, Zorro. After 32 years with the company, Sam McKim retired in 1987.

|

| Sam McKim and his Frontierland art for the Pendleton Woolen Mills. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Image of the 1961 Disneyland map is used through the Creative Commons license and is courtesy of Wishbook. Disney Legend photo of Sam McKim is courtesy the Walt Disney Company. Other photos are the property of the Disney History Institute.

Great article! Love learning some more about his process.

I loved reading this article! I have one of the vintage maps, a 1962 blue border. It is hanging in my dining room, mounted in a gold frame. I love starring at it! Thank you for sharing!

Thank you both for your kind comments. I agree. I have four of the maps hanging in my office (two McKim and a later Campbell and an Epcot map). And one McKim 1958 map in a hallway to my office. I am often sidetracked by just “stopping for a moment” to examine the map (which is probably why I get less writing done for DHI — blast you Mr. McKim!). Thanks, Paul