DHI Myth Busters Edition:

The Truth about the Petrified Tree

By Todd James Pierce

[This article is also available in an audio edition as part of the DHI Podcast – click here]

Out in Frontierland stands the five-ton remains of a petrified redwood tree. The official story, as told by the Walt Disney Company and others, goes something like this: In 1956, for his thirty-first wedding anniversary, while vacationing in Colorado, Walt purchased for his wife, Lillian a fossilized tree stump, a magnificent specimen, millions of years old. Walt arranged for it to be shipped home. But Lillian didn’t much care for this odd gift, so the following year, in 1957, she presented the tree to Disneyland and reportedly joked that the stump was “too large for the mantle” at home. In support of this story, at the base of this fossil, was placed this plaque: “Petrified Tree from the Pike Petrified Forest, Colorado…Presented To Disneyland by Mrs. Walt Disney, September, 1957.”

Now for the big question: Is the story true? Not the part about “the mantle,” the part about the anniversary gift. Was this enormous fossil really an anniversary gift that Mrs. Lillian Disney shifted from her home over to the park?

To understand how a five-ton petrified tree eventually arrived at Disneyland, you need to remember that Disneyland back in the 1950s was different than the park as it exists today. You’ll need to peel away the rollercoasters and thrill rides, the pirates and ghosts as well. Disneyland existed, largely, as a cinematic theme park, a series of lovely outdoor sets, most dressed and propped with antiques. Part of Disneyland even presented itself as a museum of sorts. On Main Street, for example, the Penny Arcade featured antique coin-operated player-pianos and self-playing organs—such as the German Orchestrion, the Nelson-Wiggen, and the Welte Band Organ. It also featured hand-cranked mutoscopes and electric cailoscopes, those early wonders of the moving picture. Out on the street itself were reproductions of streetcars, a horse-drawn fire truck, and a horse-drawn surrey—all of them presented somewhat in the style of the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village.

|

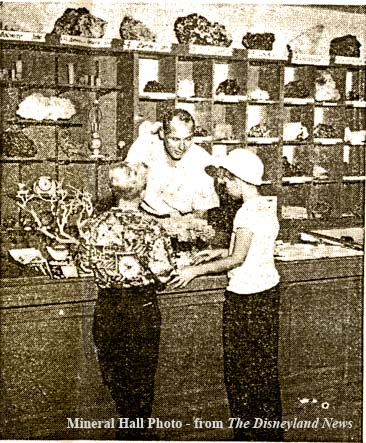

| Souvenirs from Mineral Hall |

But more to the point, for our story, in June and July, 1956, Disneyland was preparing to open an actual natural history exhibit in Frontierland, a building called Mineral Hall. Mineral Hall was to include a display of rare rocks and minerals, presented in a fashion similar to the Los Angeles Museum of Science and Industry, with a special backroom to demonstrate how fluorescent minerals took on a lovely iridescence under black lights. A gift shop area in the building would sell souvenir minerals, originally priced between a dime and fifty cents, in packages labeled Walt Disney’s Mineral Land.

|

| The Broadmoor Hotel – Colorado Springs |

During the summer that Mineral Hall was to open, Walt Disney vacationed with his wife, Lillian in Colorado Springs, a trip that fell roughly around the date of their thirty-first wedding anniversary. They stayed at the Broadmoor, a grand hotel at the foot of Pikes Peak. The hotel itself was modeled after European resorts, with touches of marble and stone, thickly-slatted wood floors, and one wing opening directly onto Cheyenne Lake.

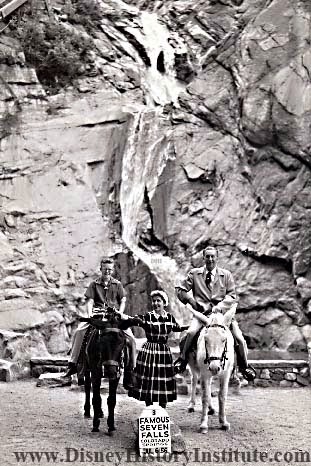

On July 6, 1956, Walt and Lillian visited a local attraction named Seven Falls, where they rode donkeys up a canyon past a series of waterfalls. Of all scenic outposts in the country, Seven Falls was the one most touched by the world of entertainment. At night, the park used stage lighting to brighten the canyon and to create a light show on the falls itself. The water was illuminated with alternating floods of white and colored light, combining a man-made spectacle with the marvels of nature. This was more or less the ethos of Disneyland itself, or at least those portions out by the Rivers of America.

That night, the Disneys would’ve returned to the Broadmoor Hotel, where, of course, Walt was recognized by a public who watched his weekly TV show. Word got around town that Walt Disney was staying at the Broadmoor. And this is where things got interesting.

|

| Walt and Lillian at Seven Falls – 1956 |

One of the people who heard about Walt Disney’s visit to Colorado Springs was John May, a businessman who had built a small, privately-own natural history museum just south of town. The May Museum was designed primarily to exhibit his father’s extensive collection of exotic butterflies and rare insects. John May invited Walt Disney out to the May Museum, with an eye toward both introducing him to his father’s gorgeous collection and hopefully renting out part of it to be displayed at Disneyland. To this request, Walt was surprisingly receptive.

A few years ago, to a reporter, John May’s daughters, Louise and Claire related the rest of the story of Walt’s visit to the Museum: “My dad was always looking for an opportunity to advertise the Museum,” Louise explained. And what better advertisement could there be for a private museum than having part of your collection on display at Disneyland?

For a couple days the May family prepared their facilities for Walt’s visit: they cleaned up the cases that held the butterflies; they tidied up the outdoor grounds. In all likelihood Walt and Lillian’s visit took place somewhere between July 9th and July 11th. Walt viewed the insects captured and preserved by the May family, probably paying special attention to the colorful butterflies. “He was very impressed with the collection, and he wanted to take it to Disneyland,” Clara recalls, though of course Walt didn’t want to display the entire collection, only a small portion of it.

|

| The May Museum – Near Colorado Springs |

But there was a problem: John May saw this primarily as an advertising opportunity. He wanted the May Museum to be credited as presenting the preserved butterflies and insects at Disneyland, while Walt wished to buy a portion of the collection outright. At Disneyland everything, except for the corporate and lessee areas, was tied to Disney. Even Mineral Hall would label its souvenirs as coming from “Walt Disney’s Mineral Land.”

“There were very intense negotiations,” Clara recalls, “and the deal fell through,” with Walt and Lillian walking away. But the event demonstrates how clearly, back in 1956, Walt believed that Disneyland might function—at least in limited areas—as a type of natural history museum.

In terms of Disneyland, the most important event of the trip happened on the evening of July 11, as Walt and Lillian were driving on a road just outside Colorado Springs, most likely with the intentions of viewing one of the privately-owned fossil grounds in the mountains. Walt eventually settled on the Pike Petrified Forest.

This portion of the story comes from Toby Wells, a boy who grew up on a ranch just east of the fossil beds. For two years, as a summer job, he worked as a tour guide at the Pike Petrified Forest. On the night of July 11, he saw a two-toned Chevy, turquoise and white, pull into the parking lot right at closing time. Though there were two people in the car—husband and wife—only the man stepped from the car. “He was a very distinguished man,” Wells recalls

Even though the charcoal tones of twilight were already pulled across the mountain, the man asked: “Can I tour the forest?”

Initially Toby Wells said no, but after considering it, he offered: “How about a small tour…I’ll still have to charge you thirty-five cents.”

To this, the man said, “OK.”

In Wells’ recollection, the man’s wife was anxious to leave, honking the horn and occasionally yelling for her husband to hurry up, but the man ignored her. Instead he expressed a desire to buy what he called “a small specimen.” Initially Wells directed the man to the gift shop where souvenir fossils were sold. Then the man clarified his intentions. “No, I want something bigger,” the man said, lifting his finger to indicate a seven-foot, five-ton petrified section of a redwood tree. “Like that stump.”

Things like the stump, Wells explained, were not regularly sold. But if the man was genuinely interested, he’d talk to the owner, John “Jack” Baker.

|

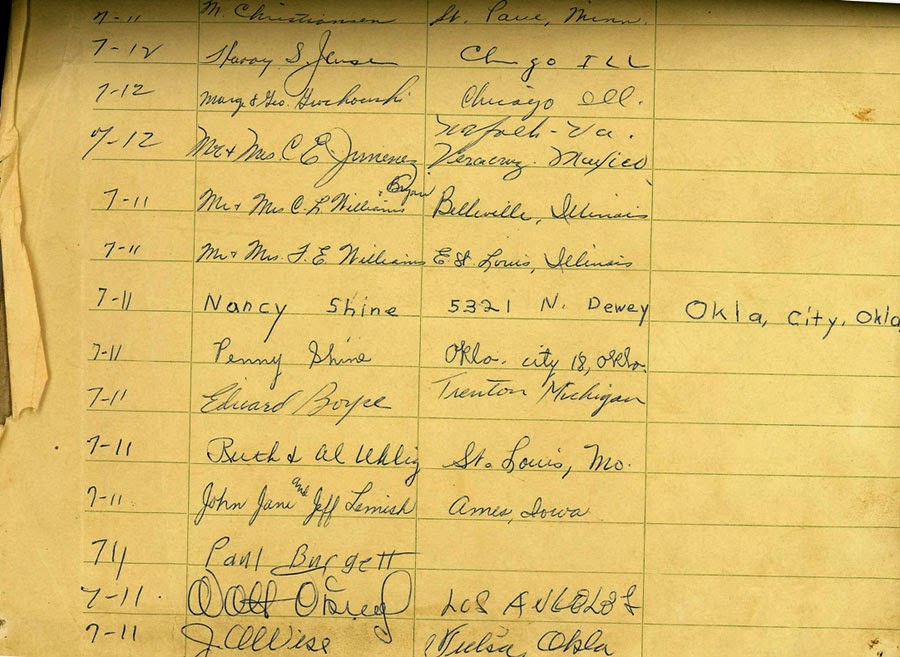

| Guestbook – 1956 |

It was then that, as the man offered his contact information, that Toby Wells learned his name. It was Walt Disney.

“I about fell over,” Wells later explained. “It blew me away.”

Before leaving, a deal was arranged to sell Walt Disney the stump. The price eventually agreed on was $1,650. Walt signed the guestbook. Then Walt and Lillian drove away.

Walt was reasonably good with people, even if he didn’t always see eye-to-eye with his wife. Most likely he would’ve understood that Lillian, who was unwilling to tour the fossil grounds at dusk, probably didn’t want a five-ton fossilized tree as a unique ornament for her garden at home.

Despite this, about one year later, Walt circulated a lighthearted story of how the impressive petrified tree had been an anniversary gift to his wife. She didn’t like it, so she re-gifted it to Disneyland, with a brass marker attached to the stump confirming these events: “Presented by Mrs. Walt Disney, September, 1957.”

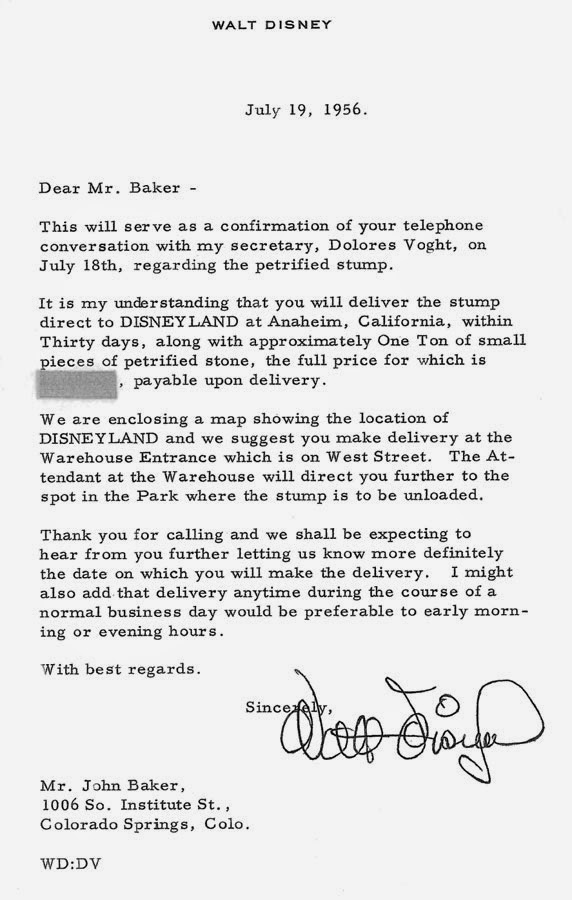

Over the following 50 years, the story was repeated, probably with some of its original playfulness drained away until it had the firm feel of history. The story was repeated most everywhere—from the official Disney Parks Blog to numerous biographies on Walt himself, including the impressive and exhaustive volume penned by Neal Gabler. In truth, I myself never thought to question the story. Hardly anyone did. We were all believers, myself included—that is, until 2009, when the family of John “Jack” Baker released a letter that Walt Disney had sent to the Pike Petrified Forest about the redwood stump.

Here is the letter:

|

| Letter – July 19, 1956 |

July 19th, 1956

Dear Mr. Baker –

This will serve as a confirmation of your telephone conversation with my secretary, Dolores Voght, on July 18th, regarding the petrified stump.

It is my understanding that you will deliver the stump direct to DISNEYLAND at Anaheim, California, within thirty days, along with approximately One Ton of small pieces of petrified stone.

The letter continues to discuss payment and optimal times for delivery and is then signed by Walt Disney. But the important part is there, in the second paragraph. The stump was never delivered to Walt’s house, nor does it seem it was ever intended to be delivered there.

But even with this information, there are still questions: did Walt initially see the petrified stump as a type of anniversary gift? Did Walt offer it as a gift on his actual anniversary, July 13, but then, after Lillian’s rejection, on July 18th, reschedule its delivery for Disneyland?

With these questions in mind, in 2010, I emailed Walt’s daughter, Diane Disney-Miller with

the hope that once-and-for-all she could solve this mystery. My email to her was fairly long,

but at the bottom, I asked my questions: I'm hoping that you can clear up a small mystery

for me…Do you ever remember that petrified tree at your parents' house in Holmby Hills?

Was the tree ever intended as an anniversary gift--with perhaps your mother quickly

telling Walt to ship it to the park? Or are parts of this story simply a tall-tale that

has grown over time?

Here is her reply:

The whole thing has been embellished. Mother and dad were driving through Colorado. Dad saw a sign that said Petrified Forest, and decided to seek it out. He did a lot of things like this. Anyway… mother stayed in the car when dad went to check it out. The owner offered to take him around the forest, and dad accepted. He was gone for some time, and mother might have been a little bit annoyed by his absence, but not seriously so. It became a family joke. He did buy that tree stump, and told her, and everyone else that it was his gift to her. Of course it went right to Disneyland. Have you seen the photo of them with it?

Then I sent her a second email, just to make sure I hadn’t misunderstood. I asked her again, if it was all a playful family ruse.

Here is Diane’s second reply:

Of course it was staged, and is very playful on both of their parts. The “gift to my wife” was just a gag. He was the consummate gag man, and proud of it. It’s difficult to believe that others didn’t see this episode that way.

So then this, it seems would be the answer: Walt used to tease Lillian by telling her that he’d bought that beautiful ol’ hunk of stone for her as an anniversary gift—a joke so obvious how could anyone see it otherwise? And then, playfully putting on the costume of the eccentric producer, he later told friends the story, perhaps as a way of provoking Lilian’s ire—possibly to get something like an “Oh Walt, really” reaction from her. And then, as he enjoyed the story, he told the world, with Lillian playing along and a brass plaque to corroborate his homemade lore.

But, of course, it was never intended as an anniversary gift. It was simply an item for the park—one of the curiosities he collected as Disneyland passed through a brief Natural History phase.

For me, there are many takeaways from this experience. First, in the half century since Walt passed away, he has been canonized as one of the men who oversaw the development of American culture in the 20thcentury. As such, it’s easy to lose sight of him as a jokester, a gagman, and a person who enjoyed a grand story. Beyond this, I see the fingerprints of Walt the person—not Walt the producer: one of the impulses that animated him throughout life was the desire to entertain others. In this story—back in 1956 and 1957—Walt pretended to be a stereotypical Hollywood producer, a man so ostentatious that he figured a five-ton tree stump would be just the right gift for his partner of thirty-one years. It was, of course, a joke—a tall-tale played out inside his family and then played out for the world. But fifty years later, sometimes it’s easier to see Walt as a legend, with all of its accompanying distance and grandeur, than as a person.

[Author’s Note: In this essay I’ve quoted from Bill Vogrin’s articles originally published in the Colorado Springs Gazette. I would like to express my gratitude to him for preserving the history of Colorado Springs and also memories of Walt Disney.]

== == == == == == == == ==

Lastly, a quick note: You can contact me through my personal webpage. My most recent book, THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success. You can find it on Amazon. And remember, even when things are a bit slow on the blog, the DHI Facebook Group is always jumping with new posts relating to the history of Walt Disney and the Walt Disney Company. –TJP

Great post, Todd J. Pierce. I know Diane really appreciated all the historians and authors who sought the real story as well as those who could recognize her father’s playfullness.

I still remember Diane telling me that Walt once reported that he asked his daughters what they’d like to see in his theme park and they told him “boys.” Diane protested and told her dad that she “never said that.”

His reply to her protest was that the press thought the story was “cute.”