|

Duck in the Hat

(or How Dr. Seuss Secretly Wrote a Book for Walt Disney)

by Didier Ghez

(or How Dr. Seuss Secretly Wrote a Book for Walt Disney)

by Didier Ghez

For years it has been assumed that Walt Disney and Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss), two of the best-known creators of children’s entertainment, never collaborated on a project. There is no project that includes both of their names; however, recently-discovered documents reveal that Geisel did secretly write one book for Disney—a book that has had a following for over 70 years. Today, on the blog, I’ll lay down how Dr. Seuss secretly wrote a famous book that, when published, only held Walt Disney’s name.

|

| Bennett Cerf |

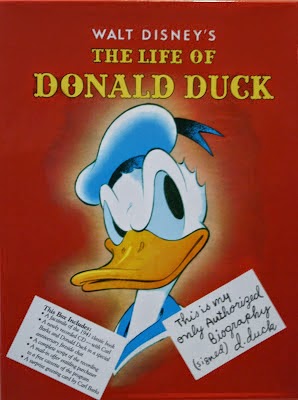

In December of 1939 Bennett Cerf, one of the founders of the publishing company Random House, and John Clarke Rose, an executive at the Disney Studio in Burbank in charge of publications, were discussing the upcoming Disney book slate. Among the ideas envisioned, several books based on Pinocchio and Fantasia, of course, but also a biography of Donald Duck titled The Life of Donald Duck, which Random House hoped to release in October 1940.

“As soon as I receive the additional Donald Duck drawings and cells that you have promised me,” wrote Cerf on December 26, 1939, “we will get to work in earnest on this book which, as you know, is very close to my heart.”[i] In the same letter, Cerf added: “The matter of the authorship of this book is still open. Robert Benchley [American humourist and star ofThe Reluctant Dragon] would be a good name, but I do not consider this important. If possible, I would like to list the book as ‘The Life of Donald Duck BY Walt Disney.’ It is understood that the illustrations for the book will be taken from old Donald Duck releases.”

|

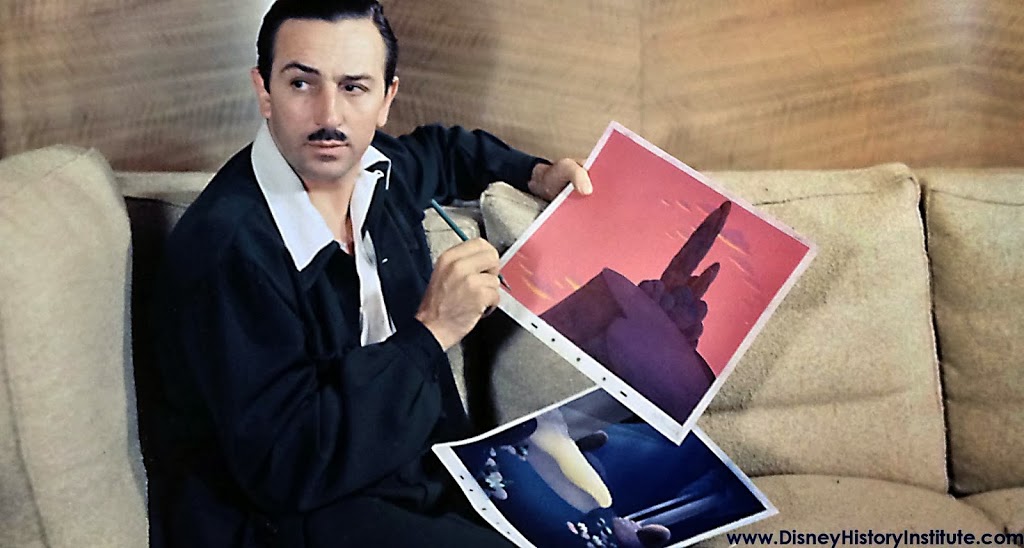

| Walt Disney, c1940 |

Four months later—after moving beyond Robert Benchley—the studio decided to create The Life of Donald Duck in house, using two storymen: Joe Grant and Dick Huemer. Joe and Dick were stars of Disney’s Story Department, men with a deep familiarity with the Duck and the Disney concept of narrative. In theory, with Joe and Dick on board, this project should’ve gone smoothly, but by the following May the book was in trouble. Even though the turn-in date was quickly approaching, the studio had no usable manuscript.

Cerf was puzzled and anxious, regularly checking with the studio to see when the manuscript might be delivered. Rose, who understood the problems, stalled and dodged Cerf’s requests. In a letter to a publicity man at Disney, Cerf wrote: “I hope you hear from the unpredictable Mr. Rose in the next day or two in regard to The Life of Donald Duck and take it you will call me about this as soon as possible.”[ii]

Four days later Cerf received news from Rose and sent him a short note which read “It is really good news to know that the first draft of the text of The Life of Donald Ducklooks swell. I still think this book is going to be a whooping success from the word go.”[iii]

But in reality Cerf had rejoiced too soon. On June 27, 1940 John Rose finally admitted that things were not progressing as planned: “Re The Life of Donald Duck: Circumstances beyond our control have delayed us and we are profoundly sorry.”[iv] A few weeks later things looked even worse when Cerf wrote to Rose: “I thought that the suggested layout and pictures selected for The Life of Donald Duck were absolutely perfect, but I am afraid that I can’t say as much for the text, which struck me as corny and singularly lacking in sparkle. I would deeply appreciate your telling me your honest opinion of this script sometime. I hope we will be able to fix it up; I think the idea is good enough to repay our leaving no stones unturned to make the product as good as we possibly can!”[v]

Replying to this note, Rose sent a rough drawing of Donald with these simple words: “Confidentially it stinks!”

On August 3, John Rose wrote tongue-in-cheek: “It would appear that nobody wants to buy a duck, or rather that our little duckling grew up to be a turkey – anyhow, Donald lays an egg!”

In that same note to Whitman Publishing executive Sam Lowe, Rose also explored other possible authors who might produce a good manuscript on the Duck: “Bennett once said he’d be willing to take a crack at the text and I wish you could prevail upon him to come to the rescue. […] I don’t think

Margaret Wise Brown is the answer. As you know, my good friend, Dr. Seuss, is visiting the family in La Jolla these days and even before you guys turned loose on me I’d confessed my worries to him. He offered me the personal Christmas present of doing the job – incognito, of course – and by golly I think he could do it if no one told his publisher and his publisher didn’t want the job himself.”[vi]

|

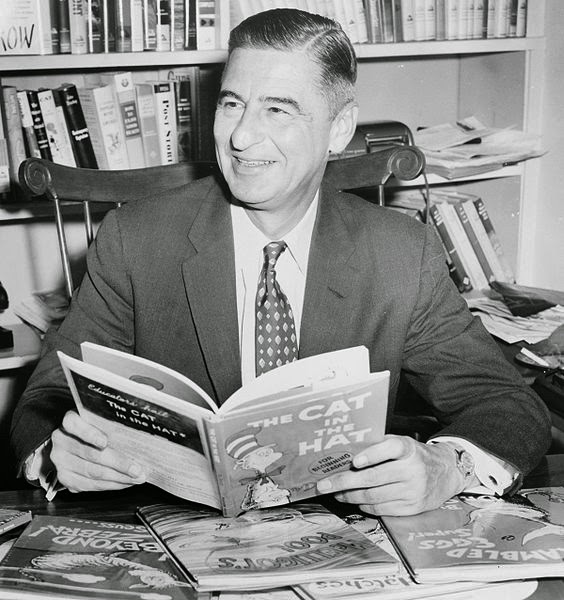

| Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss) c1957 |

To understand why Theodor Geisel would even consider tackling the Disney job—in secret, as a personal favour to Rose—one has to circle back to the late ‘20s and move from Los Angeles to New York.

In 1927 Dr. Seuss, fresh from his college years at Dartmouth, was still unknown, living with his parents in Springfield, Massachusetts, and had placed only a few of his drawings in magazines and newspapers. But on July 16, 1927 he sold a cartoon to The Saturday Evening Post, which gave him the confidence to move to New York to try and kickstart his career. In New York, Geisel moved in with an artist friend from his Dartmouth undergraduate days… John Clarke Rose, who had a one-room studio in Greenwich Village.

Here is the way Dr. Seuss himself told the story to the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine in April 1976: “The last thing we used to do at night was to stand on chairs and, with canes we’d bought for that purpose, play polo with the rats, and try to drive them out, so they wouldn’t nibble us while we slept. God! What a place.

“And I wasn’t selling any wares. I tried to do sophisticated things for Vanity Fair; I tried unsophisticated things for the Daily Mirror.

“I wasn’t getting anywhere at all, until John suddenly said one day, ‘There’s a guy called ‘Beef Vernon,’ of my class at Dartmouth, who has just landed a job as a salesman to sell advertising for Judge. His job won’t last long, because nobody buys any advertising in Judge. But maybe, before Beef gets fired, we can con him into introducing you to Norman Anthony, the editor.'”

The result of the Geisel-Anthony meeting was the offer of a job, as a staff writer-artist for the humor magazine, at a salary of seventy-five dollars per week—enough encouragement to cause Ted Geisel and Helen Palmer to marry. The wedding took place at Westfield, New Jersey, on November 29, 1927.[vii]

In other words, Geisel owed Rose not only his first job but also, to some degree, his wife. No wonder they stayed good friends. No wonder Dr. Seuss may have felt that he owed John a favor.

|

| Walt Disney c1940 |

Thirteen years later, in 1940, Bennett Cerf was ecstatic to have Dr. Seuss secretly pen the Disney Duck book for Random House: “I honestly think that Ted Geisel could do a magnificent job on the text of The Life of Donald Duck. Did you discuss the question seriously with him back here? If he won’t tackle it alone, maybe he will consider doing it jointlywith me.”[viii]

“I was also serious about Geisel,” Rose wrote, “but I hesitate to impose on his generous good nature. You see, he knew I was worried about the text, on account of he’s visiting my family in La Jolla and can hear me talk in my sleep when I join them on weekends. He would be making a personal gesture to me and would not expect any compensation.”[ix]

A week later Cerf wrote back: “I will be looking forward to seeing what the unpredictable Doctor produces in re The Life of Donald Duck.”[x]

On August 19, John Rose explained with clear delight: “You will be pleased to know that the unpredictable Doctor is sitting in my office [at the new Disney Studio in Burbank], hard at work on The Life of Donald Duck. He has already made himself quite at home here at the studio and intends to toss the medicine ball around this noon in our new Penthouse Club. If all goes well on this project, Ted may be assigned to other Disney book projects.”[xi]

“I will be holding my breath until I can see the Seuss version of The Life of Donald Duck,” answered Bennett.[xii]

“I can tell you more about the Seuss version of Donald’s Life after this weekend. Too bad you aren’t out here collaborating with Ted on La Jolla’s sands,” shot back Rose.[xiii]

When Cerf got Dr. Seuss’s text he loved it and knew that all of the problems with the old manuscript were now fixed: “Ted Geisel’s version of The Life of Donald Duck is just about a dream come true. That book is going to be a honey.”[xiv]

When Cerf got Dr. Seuss’s text he loved it and knew that all of the problems with the old manuscript were now fixed: “Ted Geisel’s version of The Life of Donald Duck is just about a dream come true. That book is going to be a honey.”[xiv]The book was released in August 1941 and remained a classic for years. In 1994 a facsimile was re-issued by publisher Applewood.

Dr. Seuss’s collaboration with Disney remained the best-guarded secret of his entire career and a total revelation to Disney historians and Seuss historians alike! Though Walt Disney’s name is on the cover, next time you see the book be sure to mentally add the name of Dr. Seuss, as his words frame the text.

Didier Ghez is the author of Disney’s Grand Tour: Walt and Roy’s European Vacation, Summer 1935 and is the editor of the Walt’s People series which collects interviews on the men and women who worked with Walt Disney and for the Walt Disney Company. He also manages the fabulous Disney History Blog.

[i] Letter from Bennett Cerf to John Rose dated December 26, 1939. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[ii] Letter from Bennett Cerf to Dick Creedon dated May 24, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[iii] Letter from Bennett Cerf to John Rose dated April 28, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[iv] Letter from John Rose to Bennett Cerf dated June 27, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[v] Letter from Bennett Cerf to John Rose dated July 17, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[vi] Letter from John Rose to Sam Lowe dated August 3, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[vii] The Beginnings of Dr. Seuss – An Informal Reminiscence by Theodor Seuss Geisel in Dartmouth Alumni Magazine dated April 1976.

[viii] Letter from Bennett Cerf to John Rose dated August 6, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[ix] Letter from John Rose to Bennett Cerf dated August 10, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[x] Letter from Bennett Cerf to John Rose dated August 16, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[xi] Letter from John Rose to Bennett Cerf dated August 19, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[xii] Letter from Bennett Cerf to John Rose dated August 21, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[xiii] Letter from John Rose to Bennett Cerf dated August 23, 1940. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

[xiv] Letter from Bennett Cerf to John Rose dated January 24, 1941. Random House Records 1925-1992. Columbia University – Special Collections.

Outstanding article. First class research. Congratulations!

Very interesting.

Of course Bennett Cerf was a well-known editor at Random House (hence the inclusion in the archive) so any anonymous work by Geisel would not have the effect of being hidden from them. They were probably trying to build up the “Dr. Seuss” name as one for children’s picturebooks at the time. Only a few large books had been published to that point (And to Think I Saw it On Mulberry Street, The King’s Stilts, The Seven Lady Godivas, and Horton Hears a Who), all published by Random House. “Dr. Seuss” would become a household name with the Random House Beginner Book series (Cat in the Hat, Green Eggs and Ham, et. al.).

Some of Geisel’s own writing was masked by Random House in these Beginner Books when he wrote the text but did not draw the illustrations. In these cases “Theo LeSieg” was used.

Another example of Geisel’s anonymous work was connected with the film and picturebook, Gerald McBoing Boing. It is now well recognized as his own work.

I’m sure that Phil Zuckerman of Applewood Books would have been glad to know of the Geisel connection with The Life of Donald Duck when he published the reprint in 1994. At the Prince and the Pauper Collectible Children’s Books during that period we were in fairly regular contact with him to locate books he might reprint, especially among the juvenile series books (Tom Swift, Hardy Boys Nancy Drew, etc.).

You are of course correct and we will modify the conclusion accordingly.

Great Job, Didier!