|

| Walt and Lillian at the Norconian – 1938 |

Walt’s Field Day – 1938

by Todd James Pierce

The most famous—and the most infamous—party ever hosted by Walt Disney was the 1938 Snow White Wrap Party at the Norconian Resort in the California Desert, a party thick with booze and brassy music, also weighted down by tense politics. Stories from that party would live on, whispers finding their way into interviews and books—whispers that have fascinated me for years.

In 1937, after the completion of Snow White, Walt celebrated with his staff at the Hyperion lot during the annual Christmas party, but at that time no one—not even Walt—could predict the enormous financial success the film would eventually achieve. By February, every showing was sold out at Radio City Music Hall in New York, with scalpers receiving up to $7.70 for reserved tickets(equivalent to $130 today). Out in California, by the second week of April, Snow White broke the Carthay Circle Theater record for longest engagement of a sound movie, with predictions that the movie would gross a third-of-a-million dollars from the Carthay Circle alone. Beyond theater receipts, the picture generated millions in merchandise sales: “Figments of Disney’s imagination have already sold more than $2,000,000 worth of toys since the first of the year,” the New York Times reported in May. In short, as one animator recalls: “The money really piled up from that movie.”

With the increased revenue, Walt expanded his staff, hiring young artists that he would train to pursue subsequent features, with work moving forward on both Pinocchio and Bambi. Walt hinted that the animators would receive bonuses for their work on Snow White, much as they had for previous short cartoons. A studio rumor suggested that the bonuses could be as much as “20% of the [movie’s] profits” given out to “all 800 employees.” Beyond this, to express his gratitude, Walt himself would host an elaborate party for the entire studio.

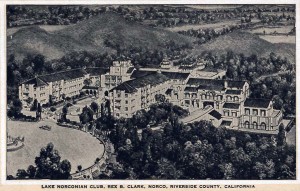

As the Hyperion lot was now too small for such festivities, Walt looked for an off-site location. He considered holding the affair at the Los Serronos Country Club—about 40 miles from the studio (in present day Chino Hills)—but he eventually settled on the more lavish—and slightly more distant—Norconian Resort. The Norconian Resort, built during the financial boom of the 1920s, featured a golf course, riding stables, a lake and marina, a massive outdoor pool with diving platforms, a ballroom, and luxury hotel accommodations. The facility, as described in a 1938 newspaper article, was proving itself a celebrity hot spot, popular “among the members of the Hollywood movie colony.” In ways, Walt was likely attracted to the Norconian because of its reputation at other studios. Disney wouldn’t be the only Hollywood outfit hosting a lavish party there in 1938. In fact, the Disney affair, with its 1,400 attendees, was small peanuts compared to the 15,000 guests that MGM would cart out to the resort later in the year.

As the Hyperion lot was now too small for such festivities, Walt looked for an off-site location. He considered holding the affair at the Los Serronos Country Club—about 40 miles from the studio (in present day Chino Hills)—but he eventually settled on the more lavish—and slightly more distant—Norconian Resort. The Norconian Resort, built during the financial boom of the 1920s, featured a golf course, riding stables, a lake and marina, a massive outdoor pool with diving platforms, a ballroom, and luxury hotel accommodations. The facility, as described in a 1938 newspaper article, was proving itself a celebrity hot spot, popular “among the members of the Hollywood movie colony.” In ways, Walt was likely attracted to the Norconian because of its reputation at other studios. Disney wouldn’t be the only Hollywood outfit hosting a lavish party there in 1938. In fact, the Disney affair, with its 1,400 attendees, was small peanuts compared to the 15,000 guests that MGM would cart out to the resort later in the year. With plans in place, Walt announced the party to his staff. He called the event “Walt’s Field Day”—a title that was out-of-step with some artists’ expectations for a grand wrap party. In the 1930s, the term “field day” defined a holiday in which school children were released for a day of athletic contests. Somewhere in this timeframe—probably during the first few days of May—Walt released a memo that explained his intentions.

In a business-like tone, a studio organizer described the Field Day as an event in which “the entire facilities of the Lake Norconian are offered for the day of June 4th. There will be no charge for either luncheon, dinner or dancing.” Additionally free use of the pool, the golf course, the ping pong tables and badminton courts would be included; however, the resort would charge a small fee for certain items: horseback riding ($1 per hour), poolside towels (10 cents each), overnight accommodations ($3.50 per room, regardless of size), and most importantly alcoholic drinks: mixed drinks would be a quarter, beer fifteen cents. In the same memo, the organizer prohibited employees from bringing their own “bottled liquor” and instead promised that the resort would have “adequate bar facilities” with drinks at reasonable prices, a plan set in place, most likely, to manage public drunkenness.

|

| Norconian Dining Hall |

None of these costs should’ve proven a problem for any studio employee. Though Walt, himself, was 36 and married, many of his artists were in their mid-20s and single. They were largely consumed by work, yet bristling with personality and enthusiasm. Moreover, since the Disney Studio was one of the few places where young artists had been constantly employed through the Great Depression, the men and women at Disney’s had both the resources and the desire to fall into such a party, especially since the studio was now muscling forward with plans for not one but two new features. This is probably where the problems began: Walt was no longer in the economic class nor the age cohort with most of the people at his studio and imagined that the lifestyle concerns of a 36-year-old film producer were also those of the young, somewhat bohemian artists he employed.

With the event announced, various studio groups had different expectations for the Field Day.

Walt and Roy—some of the married artists as well—foresaw a leisurely outdoor event, one that would appeal to middle-aged family men, similar to the social festivities held by other studios. In a May 2nd letter, Roy Disney told one of his staff members, George Morris that the Field Day would be “a general good time” and that “it might be well for [Morris],” who often traveled, “to be back here on that day.”

The newest hires, most of whom were teenagers or in their young twenties, viewed the party with wide-eyed yet respectful excitement. Having arrived at Disney’s after the release of Snow White, these recent hires had no memory of previous studio parties—including the 1937 Christmas party, which was remembered by most as a heavy-drinking affair.

The last group—and the group around which the most famous stories are focused—were those men and women who had worked at the studio for years and who, with their artistic brilliance, felt secure in their jobs as Disney artists. Included here would be men such as Ward Kimball, Freddie Moore, Frank Thomas, Art Babbitt, and Ollie Johnston. Together they had worked on Snow White, a monstrous achievement, and now struggled to produce subsequent features, films that needed to live up to the studio’s growing reputation. Members of this group (or at least some of them) also believed that Walt would use the Field Day to announce the long-promised Snow White bonuses. By this time, concerning the bonuses, Bob Givens told me, “There were great expectations.”

With this, the two main components were in place to create the Norconian fiasco: (1) Employees saw the party as a company-sponsored event to let off steam from the tremendous pressure of simultaneously starting two new features immediately after Snow White: “The poor guys,” one artist explained, “were exhausted.” (2) Beyond this, some longtime employees thought that Walt would surely use the company picnic to make good on his promise that the enormous profits from Snow White would trickle down to the artists who created the film.

|

| Field Day Memo |

On May 10th, a lighthearted and humorous memo—arranged as a story treatment—was distributed through the studio, one that appeared, essentially, as a practical joke. This new memo offered an irreverent re-introduction to the party: “Walt is playing host,” the memo began, “at an old fashioned picnic – field day – strawberry festival – quilting party – or name it.” The point, of course, was that a field day was at best an outdated arrangement for a party, one that belonged to the early 1900s, not to the modern world of 1938.

The following paragraph struck a note of sexual play: “Married couples within the studio, we’re sorry to say, should consider each other as their one guest for the day. In other words, it serves you right.” The implication, of course, was that the Field Day—at least for bachelors and bachelorettes—would have strong overtones of flirtation and romance.

“All fillies,” the memo advised, were to come in “informal attire” suitable for a big party. The memo continued: “Of course, if you want to be glamorous in a little satin or velvet guimpe for your favorite animator, that’s your privilege.” Glamour here was sarcastically described as a “guimpe,” which was both a high-collared dress that covered the whole body and also the collar piece in a nun’s habit. Again, the message was clear: Girls, loosen it up with a sexy, little outfit.

In terms of drinking, the memo advised everyone to bring a “Bromo-Seltzer bottle in your knapsack.” Though Bromo-Seltzer was once a popular cure for indigestion, by the 1930s, especially among the younger set, Bromo-Seltzer was widely used as a hangover remedy—so much so that magazine ads throughout the mid-1930s pitched Bromo-Selzer as just the thing to clear up “that morning-after fog!”

In terms of drinking, the memo advised everyone to bring a “Bromo-Seltzer bottle in your knapsack.” Though Bromo-Seltzer was once a popular cure for indigestion, by the 1930s, especially among the younger set, Bromo-Seltzer was widely used as a hangover remedy—so much so that magazine ads throughout the mid-1930s pitched Bromo-Selzer as just the thing to clear up “that morning-after fog!” In response, as animator Bill Justice recalls, Walt and Roy “sent out a memo that if you were in animation you weren’t supposed ‘to dip your pen in the company’s ink and paint’ which was their way of saying, ‘behave yourself with the Ink and Paint girls.’” Furthermore the hotel rooms, animator Ward Kimball recalls, were divided by gender: first floor, single men; second floor, single women; third floor, married couples only. When I asked animator Willie Pyle about romantic connections at the party, he explained that many younger animators felt that there was a fundamental inequality in Walt’s request. After all, he told me, Walt Disney himself “married one of his ink and paint girls.”

A final studio publication, a brochure highlighting athletic contests, distributed a few days before the event, reminded Disney personnel that “the Field Day is a party for adults only—Please do not bring any children.” With the emphasis on an adult outing, some of the animators now conspired to play a joke on Walt. Both Ward Kimball and Art Babbitt, in separate interviews, have taken credit for arranging this prank, though the truth—I suspect—is that this was a collaborative effort among many artists: In the version told by Ward Kimball, he hired an actor to dress up as a policeman and, after dinner, “harass Walt that the party was too noisy and he would have to take them all in to jail.” In the version told by Art Babbitt, Ward Kimball didn’t hire an actor at all, rather Babbitt himself “made an arrangement with the policeman on duty there.” Regardless, the idea for this practical joke—with or without a paid actor—was probably in place before the event itself.

On Friday, June 3—long before the party officially began—the staff of the Norconian Resort placed barriers on access roads to keep away sightseers and curiosity seekers.” The Norconian staff had previously hosted parties for other studios and assumed (albeit it wrongly) that a Disney Studio party would include—as one newspaper predicted—“hundreds of movie actors and actresses” to create this memorable event.

The event, of course, would be memorable, but not for the reasons assumed by the Norconian staff and the local paper.

That evening a small group of Disney employees arrived at the hotel and checked into their rooms, where they rested up for the big day.

The following morning, starting around dawn, carloads of artists headed out toward the desert. “I went up early Saturday morning,” Katherine Kerwin, an ink and paint girl remembers, “very early, with a friend.” The artists looked forward to a good weekend—perhaps a crazy weekend with a lot of drinking, hopefully some mention of bonuses as well.

|

| Norconian Pool – with Diving Exhibition |

By all accounts, Walt’s Field Day got off to a fine start. There was a golf tournament, relays down the chlorinated lines of the swimming pool, and a diving exhibition with professionals up on the boards: twists and tucks, men twinned on the platform, synchronized swanning through the air. A few of the divers—as part of the show—likely performed pratfalls and comic tumbles into the pool. Once the exhibition was over, men from the studio were invited to show their stuff on the high board. Only one animator—Milt Neil, “The Duck Man”—pulled himself up to the 10-meter platform, a precipice as high as the hotel itself: he took in a breath, steadied himself, then arced down to the water below.

The early afternoon events, it appears, all went off without a hitch. Oddly, Walt, himself, missed all of this. He was unable to attend the daytime events because, back in Los Angeles, USC was conferring on him an honorary master’s degree as part of their graduation ceremonies.

The local paper—the Corona Daily Independent—sent over a reporter to cover the festivities. “Walt Disney and his party,” the reporter noted, “will not arrive until six o’clock this [Saturday] evening.” So in Walt’s absence, this reporter followed Walt’s older, more reserved brother, Roy from event to event. Roy—who was rarely attracted to large social gatherings—appeared to have a fantastic time: “Roy and party arrived at ten o’clock and lost no time entering into the festivities of the day. He took part in most of the contests and proved himself a real sport. It was quite evident that he was much of a favorite among the hundreds of sports-loving people as he traveled from one game to another.”

Sometime in the afternoon—with the picnic lunch over—the drinking began in earnest. Harry Tytle, a production assistant, later claimed: “The big picnic quickly got out of hand.” Another animator offered a similar explanation: “by the end of the first evening, something snapped.” Ruthie Thompson, an ink-and-paint girl, recalls: “There was a lot of booze there, and it was evident.”

|

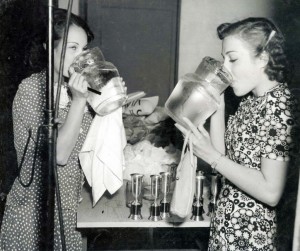

| Water and Trophies |

One animator “fell into the pool”—most likely drunk—and had to be “put to bed after that.” Bill Justice recalls that another fellow “picked up an ink and paint girl and dumped her into the pool fully clothed, followed by others jumping in and all hell broke loose pretty quickly.” One studio employee, background painter Maurice Noble recalls that one of the Disney men rode a rented trail horse into the hotel lobby. In a slightly different version of this story, the horse-and-rider also galloped up the stairs to the second floor as well. In yet another version—this one told by layout artist Bob Givens—animator Riley Thomson rode this horse into the pool.

The horse wasn’t the only animal to make an appearance at the picnic: someone guided over a field donkey or two: “I got a little tipsy,” admitted ink and paint girl, Ruthie Thompson. “I tried to ride the donkey. I didn’t fall off, but I came close to it. Somebody got a picture of me with one foot up in the air.”

|

| Walt at Dinner |

With the party bristling toward adolescent wildness, Walt and Lillian finally arrived at the Norconian just before dinner. In one version of this story—probably stemming from Maurice Noble—Walt was so shocked “by the scene that he turned around and went home.” This version has been repeated in more than one book, but it certainly cannot be true, at least in a literal sense. Photos and home movies exist of Walt attending dinner and drinking with the men afterwards. In my opinion—during the days of event planning—Walt likely saw the sexualized parody memo. Walt understood the pressure under which many of his men worked. Walt probably understood that this party would have some wildness in it—especially after the drunken escapades of the previous year’s Christmas party. What he didn’t expect was how far this party would exceed the wildness of previous events.

|

| Walt (with Cigarette) and The Practical Joke |

After dinner—as captured in home movies—Walt talked, drank and smoked with animators, the ink and paint girls as well. When Walt was seated at a table, with a group circled around him, Art Babbitt snuck away to film the practical joke he had planned with other men. A man in a police uniform, a thick badge on his shirt, approached the table and placed his wide, heavy hand on Walt’s shoulder, causing him to look up with concern. “Well, by the time the guy finally showed up,” Ward Kimball recalls, “Walt was so drunk himself that he kept arguing with the policeman and telling him he was going to have his badge.” In the version told by Art Babbitt, Walt’s tone was deep, even angry, repeating that line over and over: “I’ll have your badge.” But home movies show Walt, cigarette in hand, joking with the cop, a big smile on his face.

|

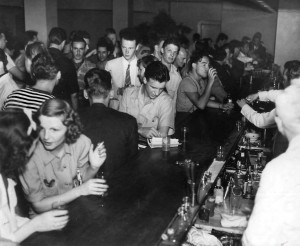

| The Bar |

Around this time, a few of the men left, perhaps sensing trouble: “I myself didn’t stay,” animator Dick Huemer said. “I left at sundown because I wasn’t there with my wife. I had to come home.”

Other people, though, were falling more deeply into the festivities: “Something just overcame everyone there,” one animator remembers, “a strange mood of excitement.”

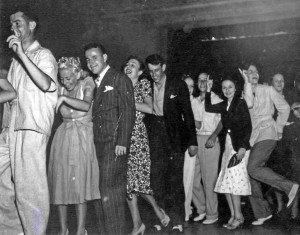

At 9pm, the event opened into a dance party—with Walt still in attendance. Although couples primarily graced the dance floor with elegant moves, film footage exists of a lead animator, Norm Ferguson dancing drunkenly with two women. The couples dance gave way to a conga line that, in turn, gave way to The Big Apple, the dance craze of 1938. “We were all doing the Big Apple,” Ward Kimball recalls. When I asked animator Willie Pyle about the Big Apple, he simply smiled.

|

| Dance Line |

The Big Apple craze started the previous year, in 1937, at an African-American dance club in South Carolina: an exuberant ring dance, something that resembled a spiritual celebration. But by the time the dance exploded into big cities—for primarily a white audience—the Big Apple had taken on sexual overtones—sort of a playful dirty boogie. At the Norconian animators swayed their hips while their feet let out a jitterbug beat. Ink-and-Paint girls shimmied their chests and whipped their hair, while the band laid down a brassy tune. But even these activities—driven by excessive drink—all seemed fairly tame compared to those things that happened later that night.

|

| Handsome Cup Trophy |

The final event was a dance contest, held at 11pm, judged in part by one of Disney’s lawyers. Once the contest was over, storyman Ted Sears took the stage to hand out awards. He offered handsome cup trophies to the winners of the golf contest and the swimming relays. Background painter Douglas “Bud” Rickert came in first in the boat race. As Sears announced the winners, the crowd’s attention slowly gravitated toward Walt Disney. Expectations swelled that Walt would take this moment to thank his artists, also to announce the promised bonuses.

When all the awards were given out, applause broke sharp as Walt stepped to the front of the crowd. The noise grew, with people slapping together their hands. A few men whistled. Then the room fell silent. Walt talked about the need for the studio to dedicate itself to the new features. He talked about the importance of the new productions. He closed by saying that he hoped this field day would move everyone to greater artistic efforts, to seize the challenges that lay ahead. No word about bonuses at all.

Studio employees clapped as Walt stepped down, but the applause, without enthusiasm, was a whisper compared to the ruckus that had carried him to the stage.

For some artists—such as those recently hired—the speech sounded like a managerial call to action. But for others—particularly those who felt Walt may be sidestepping the bonus issue entirely—the speech held the bitterness of a small betrayal.

The reasons as to why the wildness continued to expand are complicated. Surely, the bonus issue contributed to the dark energy that fed the night. Some men expecting bonuses speculated aloud that this party was all the reward they would receive after years of work on Snow White. But Bill Justice had a slightly different explanation as to why the party spun out of control—specifically long-term constraints from feature work: “For two years, all of us had been under terrible pressure, working long hours day and night to finish Snow White.”

|

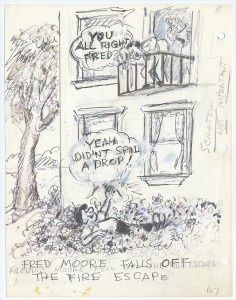

| Drawing of Freddie Moore – by Jack Kinney |

In the pool, at probably about this time, though maybe earlier: “Swimsuits flew out the windows. There were naked swim parties,” Bill Justice later revealed. One animator, Freddie Moore, the man who single-handedly redesigned Mickey Mouse, got so drunk he fell out of a second-story window—or in Jack Kinney’s version (which seems more plausible) he fell off of a second-story balcony and fire escape. Moore’s fall, according to multiple witnesses, was broken by a tree, leaving him in such good shape that he later appeared at the ballroom to dance.

Under the darkness of a near-moonless sky, animators and inkers paired off, drinks in hand, and sought out empty beds, disregarding the gender rules assigned to each floor of the hotel. “People got drunk,” Bill Justice remembers, “and were often surprised what room they were in and who they were sleeping next to when they awoke the next morning.” Another animator, Ken Anderson recalls that some of the fellows even swapped wives, an arrangement that, as a family man, offended him.

|

| The Party in the Ballroom |

These events likely took place away from the big ballroom. Willie Pyle, a young animator who spent his night at the dance, told me “I didn’t see [any of those escapades]. I never knew if it was true… I heard later that Walt was ashamed of that party. But he didn’t act like it [that night].”

Bob Givens, a slightly more experienced artist, had a different reaction: “It was a disaster,” he said.

In terms of creating a socially-respectable gathering, the event failed miserably. The party also lessened, in some ways, the loyalty certain men felt toward the studio. But in terms of creating an event in which burdens fell away from artists, “perhaps it served its purpose better than even its creator imagined.”

Walt, likely, witnessed some of the late night bad behavior—with some of it apparently pointed out to him by the hotel staff. Bad behavior he didn’t see firsthand might have reached him by way of rumor. Bill Justice later explained, “Walt was horrified at the shenanigans” as though events at the Norconian crossed some important line of morality and civil behavior. “He and his wife drove home that next morning. He never referred to that party again, and in fact, if you wanted to keep your job, you didn’t mention it either.”

Some of the men and women remained at the Norconian Resort all Sunday. With the official party over, they were now charged for all of their activities, assuming they felt well enough to participate in them: 35 cents to swim; 25 cents to putt on the green. Beer, for those who wanted to drink, remained 15 cents. By the end of the day, as Bob Givens recalls, the Norconian staff “kicked us all out of there.”

In the weeks that followed, some longtime animators sensed that the studio was changing, losing the sense of connectedness and purpose that once defined it. The Norconian party, in small ways, nudged forward those changes—changes that would eventually grow toward the famous Disney strike in 1941. But on that Sunday morning, as the big night smoldered into memory, these men and women were still mostly unified under a common cause, drinking Bromo-Seltzer, wishing away the booze, perhaps sipping down a bloody mary. Together, they were recovering from the party that celebrated the completion of Snow White, a party that they would remember for the rest of their lives.

Notes: Today’s article relied heavily on interviews and first person accounts of the party. Some of the interviews I completed myself. But this article owes a large debt to interviews completed and published by other historians–especially Jim Korkis, Didier Ghez, and Paul F. Anderson. And a very special thank you to Ed! If you are interested in exploring interviews with the men and women who worked with Walt, you can find hundreds of intriguing entries in the Walt’s People series–with Volume 13 recently published. This article is also available in an audio format as part of the DHI Podcast. Links to DHI Podcast:

iTunes: http://tinyurl.com/j34rl38

Stitcher: http://www.stitcher.com/s?fid=85297&refid=stpr

GooglePlay: http://tinyurl.com/jurtey3

I-Heart-Radio: http://tinyurl.com/zlnbn5a

Stitcher: http://www.stitcher.com/s?fid=85297&refid=stpr

GooglePlay: http://tinyurl.com/jurtey3

I-Heart-Radio: http://tinyurl.com/zlnbn5a

Lastly, a quick note: You can contact me through my personal webpage. My most recent book, THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success. You can find it on Amazon. And remember, even when things are a bit slow on the blog, the DHI Facebook Group is always jumping with new posts relating to the history of Walt Disney and the Walt Disney Company. –TJP

Recent Comments