The Original Windows of Main Street

by Todd James Pierce

So here’s the big question for today’s blog post—which windows were at the park on opening day in 1955? And what might this tell us about how Walt understood the purpose of the name windows?

|

| Main Street Window Display – October 1955 |

Now a little background: last week, I posted up a story that Harper Goff told a year before his death (in 1992) about the Windows on Main Street. Goff, as you probably know, was one of the original art directors for Main Street and the Big Kahuna overseeing the creation of the Jungle Cruise. To recap, here’s Goff’s story in his own words: “Some ground floor shops still had interior construction underway after the park was opened to the public…We would put up a serious looking sign that might say ‘Harper Goff will be opening his shoe store here soon’…but there was nothing inside the store…That was the beginning of the tradition of name signs on the windows.” Then Jason (aka Progressland) posted a question that made me reconsider what I thought I knew about the tribute windows and when they arrived on Main Street.

I knew that the Main Street Bank windows were old and dated back to an early portion of the park’s history, perhaps even opening day. But beyond that, I had very little idea as to when the other windows appeared. There was one quote by Marty Sklar that I’ve always wondered about: “The tradition [of the tribute windows] was established by Walt Disney for Disneyland Park. He personally selected the names that would be revealed on the Main Street Windows on Opening Day, July 17, 1955.” Until this week, I’d assumed he was referring only to the Bank windows. But I was wrong.

Over the past week, I’ve looked at every photo I own of the park in 1955, as well as every reel of 1955 film. I’ve also looked at every published photo I could find, including many on Daveland’s and Matterhorn1959’s excellent sites. What I learned surprised me.

Today’s post is a work-in-progress. I do not yet have all the answers. Ultimately, this will take a while to piece together. I suspect, too, that the Walt Disney Company doesn’t have the answers either, as early park records are patchy at best. I’ve been to many online sites that list the windows and offer brief bios for each person honored on Main Street, but I’ve not yet seen a site that has assembled a list of windows authorized by Walt personally or that offer a theory as to Walt’s intentions with these windows. If you know of such a site—particularly one that dates the windows—please send the web address my way, as that will save me a lot of time.

So buckle up. Here we go.

To begin, there were two windows present in the park in 1955 that were later removed or perhaps altered.

The first of those missing windows is not surprising, the window honoring Nat Winecoff. Winecoff did a lot of early work with the planning of Disneyland—specifically with locating Disneyland on property that could be annexed into Anaheim. Buzz Price oversaw much of the location study, but Winecoff pulled together a deal with Anaheim city manager, Keith Murdoch and chamber member, Earne Moeler to place the Disney park in Anaheim. But after Winecoff left Disney, he formed a consulting firm to design Disneyland-style parks elsewhere in the United States, with Bible Storyland being the most notorious of his (unbuilt) creations. After 1957—when he likely separated from Disney—he would return to the studio lot (to the model shop, in particular) in an attempt to hire away Disney talent. Bruce Bushman, for example, finally signed up with him. Winecoff also had the reputation of hiring attractive women to help close some early Disneyland sponsorship deals, a practice that probably didn’t sit so well with the brothers Disney. The exact quote I heard in regards to these meetings was that “Nat knew where all the [girls] were.” So that his window disappeared—no surprise. The Stuff from the Park blog has an excellent close up of the window here and then here.

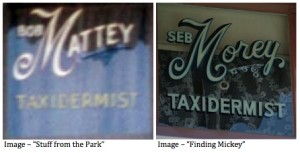

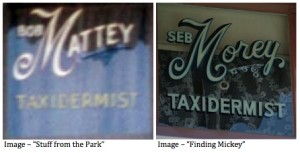

That leads us to Missing Window #2. Also to an actual mystery–a big one, in my opinion. Bob Mattey’s window—which listed him originally as “Bob Mattey / Taxidermist” appears to be gone. (Just click here to take a look at it—trust me, you’ll need that image in a moment.) Maybe I’m out of the loop on park gossip circa 1955, but I’m totally baffled as to why Mattey’s no longer honored in the park. Mattey arranged all of the animatronic movements for the animals in the Jungle Cruise (though he did not actually sculpt the animals himself. Chris Mueller did that.) So the fictitious title of “Taxidermist” fit his job description fairly well: he made fake animals appear real. Beyond the Jungle Cruise, Mattey created special effects for at least 15 Disney films, up until Walt passed away, including 20,000 Leagues, The Absent-Minded Professor, Babes in Toyland, The Gnome-Mobile, Mary Poppins, and The Love Bug. Again, the Stuff from the Park blog has an excellent photo of the window bank in which Mattey’s window used to be displayed.

Now for the weird stuff. The Bob-Mattey-Taxidermist window has been replaced with a window (with the exact same layout) for Seb Morey / Taxidermist. Click over to Daveland’s site for a nice close-up. Now for a confession: aside from this window, I’ve never heard of Seb Morey. And when I click around the net, most all of the sites I can find simply parrot each other. (site 1: “Seb Morey was Disneyland’s original taxidermist. Skilled in his art, Morey worked to create lifelike figures for the Jungle Cruise.” site 2: “Seb Morey was Disneyland’s original taxidermist and did a large portion of the work on the Jungle Cruise.” site 3: “Original taxidermist for Disneyland; did much of the work on the Jungle Cruise.”)

Here’s where things get even more strange: It’s possible that Seb Morey worked with animal figures at the park. The park actually employed a taxidermist, but from 1963 through the mid-1980s the actual “taxidermist” was a man by the name of Bob Johnson. Johnson’s official title was “Staff Shop Artificial Taxidermist,” which generally meant that he repaired fur and feathers on artificial animals installed at the park. He more or less ran that division for 25 years. Before Johnson, Disneyland employed at least one traditional taxidermist to care for the early animal figures that the park covered with real animal hides–mostly in Frontierland. But that apparently wasn’t Seb Morey either. In a 1977 interview, Bob Johnson explained what happened to the park’s previous taxidermist: “The real taxidermist left because his experience was with the real stuff,” wishing not to work on animal figures now covered with more durable synthetic hides.

So who was Seb Morey?

Though there may be other sites that have helpful information, the only one I could find on the Morey issue was Daveland’s site. (Dave, you do excellent work!) Here’s what Dave has: “’From his daughter-in-law: ‘His full name is Sebastian Moreno and he worked at Disneyland for about 38 years as a decorator. He was a department supervisor for many of those years and was known to his colleagues as Morey. He started working there in 1955.’” From that, I was actually able to find an obit on Sebastian Reyes “Morey” Moreno. Not surprisingly, the skill of “taxidermy” is not mentioned in this lengthy obit, not anywhere. Here are the sections that pertain to Disneyland: “Sebastian spent most of his life in Fullerton, California. He spent summers as a youth with his family picking crops to earn extra money. After high school he worked on the Santa Fe railroad with his father Ramon Moreno. His ability to speak fluent Spanish and English was utilized by the U.S. Army when he served as an interpreter for a Battalion from Columbia during the Korean War. After his discharge from the army his experience working on the railroad helped him land a job at Disneyland working on the railroad being built around the park. He soon became a member of the renowned decorating department at Disneyland where he rose through the ranks to become a decorating supervisor until his retirement after 38 years. He loved the Park and all of his colleagues.”

At my request Jason Schultz, of the excellent blog Disneyland Nomenclature, has searched through his holdings for references to “Seb Morey”, only to find the only reference to Seb Morey is in regard to the window. Sebastian “Morey” Moreno, however, is listed as a Disneyland employee starting in 1956, receiving his five-year pin in 1961, and is included in the Disneyland telephone directory until June 1993. The only substantive description in the weekly company newsletter, The Disneyland Line, for Sebastian “Morey” Moreno was printed in 1976: “Sebastian ‘Morey’ Moreno has been with the Park since 1956, and during his first years in the [Decorating] Department he became acquainted with some of the early Disneyland designers, especially Emile Kuri.” And this, in my opinion, makes a good deal of sense, as Emile Kuri–perhaps serving as a type of mentor–would’ve been able to train Morey in interior set dressing so that Morey could later become a decorating supervisor. The work of set dressing (overseen by Emile Kuri), needless to say, is very different than the work of motorized animal development (overseen by Bob Mattey).

All of this begs the question: why (and when) was the window changed from Bob Mattey / Taxidermist to Seb Morey / Taxidermist, with the giant “M” remaining the same, right down to the oversized serif and the curlicue feet. It’s on the same building: the current Morey window is actually one window spot to the right of the original Mattey location, but that’s not surprising as other windows in the block (with their names unchanged) have shifted location as well. So why did Bob Mattey morph into Seb Morey—with only a few letters separating the two names? A person who spent 38-years with the company to eventually become a supervisor in the Decorating (i.e. the propping) department certainly deserves respect. That, in itself, is a substantial accomplishment. But it would be interesting to know why Mattey became Morey. And I must say, that the Mattey/Morey replacement (being nearly identical) does seem a little curious to me. I can think of no other window in which the original honoree was replaced with a later honoree (with the fictitious title and design work remaining the same). The Bob Mattey window is an original 1955 tribute that exists at the park up through 1969, perhaps longer, though 1969 was the last image I could find of the Mattey window. I suspect there’s a really good story here, only I don’t know it. I’m hoping that a few blog readers might help sort all this out.

So, now for the larger question: what other windows were in the park on opening day, and what did these windows signify? (I’m going to focus my attention only on those windows assigned to individuals who worked on the park, leaving aside “vanity” windows, such as those outside the original Upjohn’s Pharmacy that listed individuals associated with the Upjohn company but otherwise had no connection to Disney).

Today, new Windows on Main Street are seen as a lifetime achievement award. But initially, for Walt, they apparently served roughly the same purpose as a screen credit—acknowledgement given to a high-level employee for work recently completed, even if that individual spent only a couple months working on Disneyland. For example, Renie Conley, the costume designer, created the show costumes for the Golden Horseshoe Review and, likely, for a few other locations in the park, such as some period costumes for Main Street (i.e. the constable) and perhaps even the spaceman’s suit in Tomorrowland. For this, she is honored with a window on Main Street. Over time, the significance of these windows increased so that an artist today, generally, would only be awarded a window after decades of service.

|

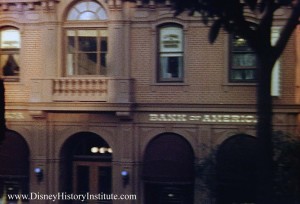

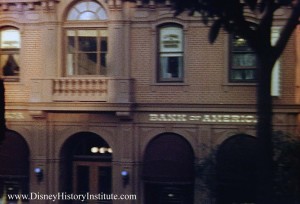

| Disneyland 1955 |

On July 17th, 1955, opening day, the bank windows were clearly in the park—I’ve located photos and 16mm footage of them—painted much as they are today. Even here, on the bank building, it is clear that Walt was grouping individuals based on their roles in park development. (Here’s a link to a fantastic opening day image on the Daveland site.) These are by far the least ornate windows on Main Street. In many ways, their inclusion seems almost perfunctory. The honorees are, largely, art directors brought in from non-Disney studios to develop Walt’s plans for Disneyland—with many of them coming from 20th Century Fox. In 1953 and 1954, Fox was struggling financially, so it was easy for Disney (with a little guidance from Dick Irvine) to cherry pick from the group that regularly worked for Fox. The list includes: Richard (Dick) Irvine, Marvin Davis, Wilson (Bill) Martin, Gabriel Scognamillo, George Patrick, and Wade B. Rubottom. But even here, the list of Disneyland art directors is nowhere near complete. These might have been the most visible—or perhaps the most senior—of the art directors plucked from other studios. Among the missing are Fred Harpman, Stan Jolley, and Sam McKim—with the most curious of the absent directors being Stan Jolley. That is, until you realize that Walt and Jolley were having a fight of sorts in the days leading up to the opening of Disneyland. In Jolley’s own words: “So I told Dick Irvine and Walt and Marvin Davis and Carroll Clark that I was going to take a two week vacation and go to New York because I had bought some tickets and I was entitled to a vacation. I was told that if I went back east and went on a two week vacation in New York at that time, don’t expect to have my job when I come back.” But when Jolley returned, he still had his job at Disney—he would develop much of Storybook Land the following year—but would have no window on Main Street. I suspect—but do not know—that the two incidents were related.

Beyond this, I’d like to make one other observation here. These art directors brought in from other studios are all likely card-carrying union members (IATSE). As such, they would have been entitled to screen credit for their work. Walt may have understood that the name windows would’ve been tantamount to screen credit for senior artists, and as such believed that there was an implied (or actual) obligation to list their names, the same as he would for his own artists on other (far more ornate) windows. In this group, there are at least two people Walt did not like: Gabe Scognamillo (whom, according to Joe Fowler, he fired after Scognamillo flexed his ego one too many times) and Wade Rubuttom (who was simply bull-headed and difficult). Art directors, generally, worked on a project-to-project or film-to-film basis, with most of them understanding that the Disneyland project was limited-time employment. Though Scognamillo was actually fired, Rubuttom was simply let go (along with many other outside artists) when the Disneyland project was finished. A few of these outside artists (such as Bill Martin) were kept on for decades.

Also in this grouping, on opening day, were three engineers: J.S. Hamel,

William T. Wheeler, and John Wise.

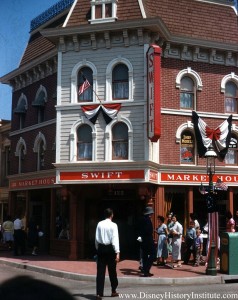

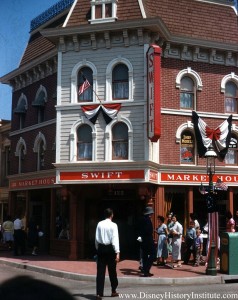

The Market House also contained tribute windows on opening day. Here, too, you can see that Walt gave some thought to the arrangement and placement of these windows. On the Main-Street side, there was a grouping of Disney art directors: Ken Anderson, Bruce Bushman and Don DaGradi. It’s fitting that Bushman and DaGradi were paired because, years earlier, they produced many of the original concept drawings for Mickey Mouse Park, that 16-acre amusement park Walt wanted to build across the street from the studio.

|

| Market House – 1955 |

On the other side of the building were Bob Mattey (see above) and George Whitney Jr, as well as the lead construction supervisors, the lead mill workers, the lead carpenters, a painting supervisor, and a brick-and-stone man. All of these windows I have spotted in photos and film shot during 1955. There were other individuals honored here (among them Bill Cottrell and L.H. Roth). In all likelihood, they were included here in 1955—only as of today, I’ve not been able to positively identify their windows in photos from that year.

So another question I tried to answer: did Walt personally add any tribute windows after the park opened? There are plenty of window’s added after Walt’s passing, but were any subsequent windows added during Walt’s lifetime? I only have a partial answer. Yes, but I’ve been able to just spot one. The window belongs to Emile Kuri, who essentially dressed sets at Disneyland. For example, Kuri bought many of the antiques that were incorporated into various shops (on Main Street) and attractions (such as Pirates of the Caribbean). In this first photo, from 1955, you can observe the lower window has no tribute illustration. In this second photo, form 1959, you can see the finished name window. Again, thanks to Daveland.

On the Carnation building, I’ve been able to find 1955 images for Renie Conley (who designed the costumes, such as for the Golden Horseshoe Review) and Royal Clark (a longtime Disney family lawyer who worked directly for WED), but I haven’t been able to find a clear photo of the window for Fred Joeger (from the Disney model shop), though it’s possible his window was present at the park in 1955.

Three of the most important artists associated with Disneyland—Herb Ryman, John Hench, and Peter Ellenshaw—are honored with a window at the end of Main Street, above the rooms then-occupied by the Insurance Company of North America, but I’ve not yet found a 1955 photo of that window. Likewise I’ve not been able to find a 1955 photo of Harper Goff’s window in Adventureland. Lastly—because of their odd placement—I haven’t yet been able to find clear 1955 photos of some windows on the East Side of Main Street, near the cinema, among them Wathel Rogers and two lawyers: Gunther Lessing and Fred Leopold.

As I reflect on those last two names, I also see that the windows on Main Street primarily honor Walt’s creative design team and the construction team. During the 1950s, the Disney studio had a clear management division between Walt’s creative team and Roy’s financial and business team. These two lawyers (Lessing and Leopold) would’ve been attached to Roy’s business team. But none of Roy’s financial men were honored at the park, even though they played a significant role in the creation of Disneyland.

There is one more group missing: the actual management team at Disneyland, most all of whom by July 1955 had worked for Disneyland Inc for well over a year. That is, longer than any of the construction workers.

The first employee and General Manager of Disneyland was a Texan named C.V. Wood, who oversaw the development of Disneyland, as a business. In other words, he sold the leases and sponsorships for the park, which brought in much needed capital to complete construction. (In one interview, he claims to have sold every lease and sponsorship, though that perhaps was an exaggeration—but probably not by much.) He oversaw the publicity for the park, food service, and souvenirs. Human resources and training (for which he hired his friend, Van France) were also under his control. C.V. Wood—as well as everyone on his development team—was excluded from this list of opening day honorees, though clearly C.V. Wood and members of his Disneyland Inc management team (specifically Charlie Thompson and Fred Schumacher) did far more to develop Disneyland than the managers of the mill and the lead carpenters. And they certainly did more than the costume designer. One of the biggest power struggles in Disneyland’s history—what Dick Irvine would later call “a knock-down, drag-out fight”—occurred between Walt Disney and C.V. Wood. What the exclusion of Wood’s team does likely indicate is how much trouble there was between Walt and Wood even as the park opened.

To circle back to the Harper Goff quote that started this post, what did his story mean—that the ground-floor fictitious business displays eventually gave rise to the tribute windows? Those 1955 ground-floor window displays clearly existed, almost exactly as he described in 1992. But was Goff thinking of people with later windows like Emile Kuri or even Claude Coats? Or was Goff thinking of something else? Of that, I’m not entirely sure, though clearly a connection exists, as those early windows were made by the artists to playfully honor themselves and the permanent windows were a gift to solidify or perhaps even re-instate the tribute.

Again, this is a work in progress. Expect changes and updates. If you have photos—or links to photos—that will help place more windows in 1955, please send them my way. Also if you can pinpoint windows (aside from Emile Kuri’s) that first appeared between 1956 and 1966 (the year of Walt’s passing), I’d appreciate that, too.

–with thanks to Jason Schultz and gratitude to the Daveland, Stuff from the Park, and Finding Mickey websites.

* * * * *

If you are new to our site, you can always find a lively and ongoing discussion of Walt Disney’s creative legacy on the

DHI Facebook Group. It’s free to join. The core group DHI authors–Paul, Jeremy and myself–often post additional photos and never-before-published pieces of artwork there. It’s worth checking out.

Great article. I know that one of the places on Main Street that was not opened originally was the Maxwell Coffee House on Town Square. It was one of the key frustrations between Walt and C.V. Wood, and Walt held him personally responsible for not getting it opened, which apparently did not happen until about Christmas. It makes me also wonder when Elias Disney was listed as a contractor. I would think this gesture came from Walt himself.

Glad to know that two people (me being the other) are baffled by Bob Mattey’s window being painted over. I’ve been working on a book about the mechanical effects team that created and controlled the sharks in JAWS for a few years now. I have a fairly extensive Bob Mattey bio which makes up chapter one.

Mattey was laid off from Disney Studios in 1970. Most of the mechanical effects work that he did in the late 60’s (after Walt) was supervised by Danny Lee with Mattey playing an almost consulting role. Not sure of the politics involved there as Lee had moved to Warners and won an Oscar for Bonnie and Clyde (67). He was also what could be considered Mattey’s apprentice. Maybe Danny was more of a studio guy than ole Bob. Bob Mattey came out of the RKO Pictures era and by the late 60’s his cute mechanical animals were replaced by hi-tech (at the time) WED animatronics. Or maybe it was Bob jumping ship to work on a Hammer Film in England in 1968 that sealed his fate.

At any rate I would be interested in reading anything if you are able to uncover the truth. My experience is that many years later folks like to retell and color their stories from their own point of view. We may never know why Bob Mattey, the man who brought a a giant squid to life, made Mary Poppins fly and gave personality to two different cars’ window is gone.

More here: the-jaws-blog.blogspot.com/