THE SUNDAY FUNNIES

|

| Click On For A Larger & Clearer Image |

WHAT WAS WALT READING?

By Paul F. Anderson

Today with the second installment of The Sunday Funnies, I kick off a new facet of this popular series of posts–“The Sunday Funnies–What Was Walt Reading?”

The initial idea for The Sunday Funnies was to show how Disney dominates our culture, through various references, appearances, or allusions in non-Disney comic strips. I thought it might be enlightening to take this a step further, and find out what Funnies Walt might be reading, or what strips may have amused him or provided a spark or idea. On the surface this sounds fascinating, but how does one actually go about discovering this information? As I thought about it, I realized that over the last twenty years of my Disney history career, I had been doing just that, without realizing what I was doing or why?

In many past research trips to the Disney Archives, I would come across “news clippings” files in Walt’s correspondence. Found within are newspaper and magazine articles that were torn (or cut) out by either Walt, his secretaries, friends, or employees. As my motto for research is “Turn Every Page” (sadly not original to me, but the philosophy of Robert Caro), I would go through every piece of paper in these files, in case there was material of interest to that which I was researching. If I found something noteworthy, I would type in the information along with any source material that might be available (and in a few situations, take note of what Walt’s familiar red conte crayon had underlined). I discovered that hundreds of days at the Archives with this particular quirk of recording items I thought might someday be useful, has resulted in quite a list of items from Walt’s clipping files. With that, and the ability recently to do newspaper and magazine research at a much more economical pace via the internet, I began hunting down some of these pieces.

So what about these files? The files are never that big, especially early in Walt’s career. However, they did tend to grow exponentially as the decades wore on. For instance, the 1938-1944 file, has perhaps 225 items in it and is about a half-inch thick (and that is being generous). The files from the mid-1960s (especially when the World’s Fair, Project Florida, and Epcot were underway) are many, many inches thick!

Walt must have been given dozens of clippings each day (NOT including the Clipping Services), so why are these clippings important? Simply put, due to the vast amount of these daily news items he received, it is logical to assume that most of them ended up being filed in the trash can! But not all of them! What Walt thought was interesting, important, historical, relevant, and/or otherwise just amusing, found their way to being preserved in Walt’s correspondence files, in a folder often titled just, “WALT DISNEY (newspaper clippings).”

Simple mathematics (which is saying something for me, as my degrees are in History), can give us a bit of perspective on the importance of these “saved” clippings. In the seven years from 1938 to 1944, there are 2557 days! Walt kept approximately 225 clippings. That is roughly one saved item every two weeks. So for whatever reason, these select few appealed to Walt. Obviously, one can not place vast amounts of importance on this theory, as who knows what errant clipping might have found its way into the files, and of course we will never know why Walt found it intriguing or worth saving. Still, it does give us a different look at Walt, one rarely (if ever) seen or discussed.

So with this essay, I inaugurate a new feature here at the Institute: “The What Was Walt Reading” column. In the future, I plan on posting the news articles with commentary, as well as the cartoon strips. Unfortunately, I did not record a large number of cartoon strips, and I don’t recall that there was a plethora of this kind of material. Typically, if there was a cartoon, it was political in nature. But I will continue to scour my notes from past Archives trips (easily over a thousand pages) in a search for more cartoon references.

|

| Crockett Johnson and his dog. Time Magazine, September 2, 1946. |

The first offering is Barnaby by Crockett Johnson, and from the Hollywood Citizen-News, April 29, 1944. (This paper can be invaluable to someone researching any aspect of Disney history, and a complete run from 1903 to 1970, in all of its incarnations, can be found at the main branch of the Los Angeles Public Library.)

Crockett Johnson was born in New York City in the year 1906, with the name David Johnson Leisk. Growing up on Long Island, he studied art at Cooper Union and New York University, and after leaving found his way into the business as an art editor for several magazines. He used the name Crockett Johnson for several reasons. “Crockett is my childhood nickname,” he recalled. “My real name is David Johnson Leisk. Leisk was too hard to pronounce, so I am now Crockett Johnson.”

|

| Self Portrait, 1941 |

Barnaby is arguably his second most famous creation, but little remembered today. However, in mid-century America, Johnson’s characters were much beloved and quite popular. The strip first saw the light of day on April 20, 1942, in the left-leaning PM newspaper (oddly famous for numerous negative reviews of Disney films). The gritty characters appealed to a country immersed in War and shortly the strip became syndicated and appeared in 64 American newspapers, with a combined readership of well over five million. The strip continued on through February 1952, with a brief, but unsuccessful, revival from 1960 to 1962. In many ways, Crockett Johnson was like Walt in the thirties, but on a much smaller scale, as he became sort of a darling of the intellectuals and artists. The habitual acerbic and biting Dorothy Parker stated: “I think, and I’m trying to talk calmly, that Barnaby and his friends and oppressors are the most important additions to American Arts and Letters in Lord knows how many years.”

The strip concerned itself with the daily trials and tribulations of the five-year old Barnaby Baxter, and his cigar-chomping fairy godfather Jackeen J. O’Malley. As the Angel Clarence was to George Bailey, so was O’Malley to young Barnaby; bumbling, incompetent, but with his heart in the right place. Many of the tough issues faced by Barnaby were the result of O’Malley, who was a sworn member of the fraternal organization of Elves, Leprechauns, Gnomes, and Little Men’s Chowder & Marching Society (affectionately known as the ELGLMC&MS). Much of the humor resulted in Barnaby sticking up for his pal, while the young man’s parents made repeated attempts to deny the existence of O’Malley, often taking the boy to child psychologists so as to be fixed. Their refusal to accept O’Malley was a running gag, as the little man on several occasions made his existence known to them, and was even elected as their Congressional Representative.

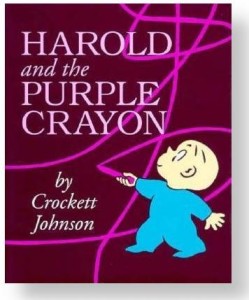

If you are under the age of sixty and are thinking that the name sounds familiar, you have probably heard of his other famous creation: Harold, of Harold and the Purple Crayon fame. This children’s book first appeared in 1955, and was followed by six more books in the next eight years. Stylistically, Harold appears to be a younger, reincarnated Barnaby Baxter, but in this case rather than the diminutive wise-cracking fairy godfather as an accomplice, Harold’s adventures come via his purple crayon. The books are still in print and a favorite among many children. (I am not aware if Walt Disney was familiar with these books, but knowing his interest in literature for children, I would suspect that he was.)

If you are under the age of sixty and are thinking that the name sounds familiar, you have probably heard of his other famous creation: Harold, of Harold and the Purple Crayon fame. This children’s book first appeared in 1955, and was followed by six more books in the next eight years. Stylistically, Harold appears to be a younger, reincarnated Barnaby Baxter, but in this case rather than the diminutive wise-cracking fairy godfather as an accomplice, Harold’s adventures come via his purple crayon. The books are still in print and a favorite among many children. (I am not aware if Walt Disney was familiar with these books, but knowing his interest in literature for children, I would suspect that he was.)I do not have any readily available answer as to what intrigued Walt about this cartoon. That will, of course, be the charm of future “What Was Walt Reading” essays, if only for the fun of speculating on Walt’s interest in an item. For most items, there will be no right or wrong; just mystery and intrigue. My hope is that some snappy dialogue amongst Institute readers might develop in the comments sections. After all, your guess is as good as mine.

But, back to Barnaby Baxter. Had this cartoon appeared a year or two earlier, I would have surmised that the production of Gremlins might have provided inspiration. Within the Gremlins files are many references to fairies, elves, gnomes, and other wee folk, much of which was intended for the Disney artists, because figuring out just exactly what a Gremlin looked like, was of paramount importance. Yet, by the time this Barnaby cartoon appeared, the animated film had been shelved.

The idea and concept does have sort of a Disney-like feel to it, and it is always possible Walt was considering, or reviewing, a similar story–that of adventures with an imaginary friend. This idea is a strong one, as can be witnessed by the success of others using it. The most brilliant use of this archetype was done for one of the best comic strips ever (and my personal favorite), Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Watterson. So perhaps, Walt was just thinking along those lines. Or, perhaps, he just liked the comic strip like many other Americans.

I am always interested in hearing comments or ideas you Disney historians and enthusiasts might have about dear Barnaby Barnaby and Mr. Jackeen J. O’Malley. And to close, I’ll make use of the “current” vernacular… “Cushlamochree!”

Recent Comments